Bond. Someone else’s idea of James Bond

Ian Fleming had a very interesting idea. It was an idea that lived for several books and a few films, but was thrown in the trash with his death ten years afterward. As the years have gone on, the Bond that Fleming imagined and designed from his estate in Jamaica in 1953 is now anathema to what we see on our screens today. What we are watching is one of the finest characters ever to be put into print, slowly morphed into an overly-safe Jason Bourne.

During the Second World War, Ian Fleming was a Commander in British Naval Intelligence, alongside his brother, Peter. Also during that time, Churchill formed the Special Operations Executive (SOE), as David Stirling cobbled together first incarnation of what we know now as Special Forces (SF), in the form of the Special Air Service (SAS).

Fleming’s character was an amalgamation of the daring “secret agents and commando types” he met during his military service, but more importantly, his character was largely based on himself: a chain-smoking, womanising, gambling-obsessed naval commander aristocrat who has the same golf handicap, taste in foods, cigarettes, and toiletries.

The supporting characters in Fleming’s novels are, of course, based on his own friends and acquaintances.

In modern times, the name “James Bond” is synonymous with the sexiest, death-for-breakfast adventure ideas you can imagine. However, that’s not what Fleming was going for.

In his own words:

“I wanted the simplest, dullest, plainest-sounding name I could find, ‘James Bond’ was much better than something more interesting, like ‘Peregrine Carruthers’. .. when I was casting around for a name for my protagonist I thought by God, [James Bond] is the dullest name I ever heard. It struck me that this brief, unromantic, Anglo-Saxon and yet very masculine name was just what I needed, and so a second James Bond was born.”

Fleming, like so many spies, was a birdwatcher. He had a copy of “Birds of the West Indies” by American ornithologist James Bond, a Caribbean bird expert. He used the name simply because it was extremely dull.

Next was his concept for Bond — again, the exact opposite of what we see today.

“Exotic things would happen to and around him, but he would be a neutral figure — an anonymous, blunt instrument wielded by a government department.”

Fleming wanted Bond to be the enigmatic antithesis of what we watch now: a typically “grey” MI6 desk spy, with the excitement happening around him. There was no prose dedicated to him swinging off trains, and he was absolutely not the centre of the action at all.

But it was actually much worse. The character of Bond himself was profoundly grey, and verging on sociopathically anti-social. Certainly not charming, debonair, or exciting. “Emotionally unavailable” would be putting it lightly. In fact, taking Fleming’s concept of “cold passion” at prime facie makes for very grim reading indeed:

“I don’t think that he is necessarily a good guy or a bad guy. Who is? He’s got his vices and very few perceptible virtues except patriotism and courage, which are probably not virtues anyway. I didn’t intend for him to be a particularly likeable person. [Bond is] a healthy, violent, noncerebral man in his middle-thirties, and a creature of his era.”

Fleming said it: not likeable, and “very few perceptible virtues”. He’s not a nice, interesting, or appealing person — that’s what intensifies the wonder of the action and backdrop in the stories.

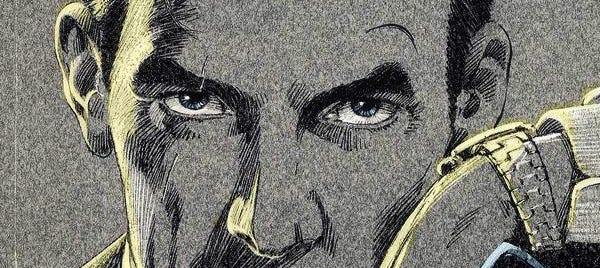

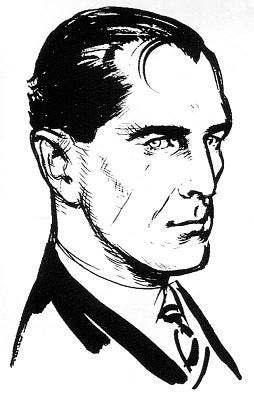

Bond himself has a very specific look, with a very specific character. Fleming sketched him:

His description is precise: slim build; a three-inch long, thin vertical scar on his right cheek; blue-grey eyes; a “cruel” mouth; short, black hair, a comma of which falls on his forehead. Physically he is described as 183 centimetres (6 feet) in height and 76 kilograms (168 lb) in weight.

The person who is repetitively referenced as the physical template or archetype for the character is singer Hoagy Carmichael:

“Bond reminds me rather of Hoagy Carmichael, but there is something cold and ruthless.” (Vesper Lynd)

“certainly good-looking … Rather like Hoagy Carmichael in a way. That black hair falling down over the right eyebrow. Much the same bones. But there was something a bit cruel in the mouth, and the eyes were cold.” (Gala Brand)

But with all descriptions of Bond, one word keeps coming up again, and again, and again, and again.

Cruel.

He has a “cruel” mouth. Again, he is “cruel in the mouth”. “Cruel” good looks. He has a scar on his cheek, and a ring of hair. This character is not likeable, and is always seen as a cold, cruel man. He earns a salary of ~$65,000 USD, lives in Chelsea, and spends his even playing cards, or seducing married women.

Let’s take the word “cruel” away from Hollywood sexiness, and be semantic about it:

“willfully causing pain or suffering to others, or feeling no concern about it.”

Fleming’s character is unlikeable, cold, addicted, and absolutely not the type of character anyone would want to date. He doesn’t “save” people or show them compassion, despite his complexity. He is a moral enigma, dressed like he’s going to Ascot.

Then, of course, we have the 007 acronym, and how incredibly wrong Hollywood now has this — portraying it as a government “program”. Q Branch is thankfully mostly unchanged, but “00” is just a serial number.

Again, the code itself is an amalgamation: SOE operatives during the Second World War were never referred by their ordinary Army serial number, but had to be given a new anonymous codename. The most secret achievements in British intelligence tended to be prefixed with “00” to indicate their level of top secrecy. Fleming chose “007” from cracking of the German Zimmerman Telegram (designated “0074”), and theorised that the prefix was the status bestowed“license to kill” (which Bond never actually did cold-bloodedly).

In 2015, this “license to kill” does has a basis in fact in a “Section 7 Authorisation”: Section 7 of the 1994 UK Intelligence Services Act offers protection not only to spies involved in bugging or bribery, but also to any who become embroiled in far more serious matters, such as murder, kidnap or torture — as long as their actions have been authorised in writing by a secretary of state.

The text reads:

“(1) If, apart from this section, a person would be liable in the United Kingdom for any act done outside the British Islands, he shall not be so liable if the act is one which is authorised to be done by virtue of an authorisation given by the Secretary of State under this section.

(2) In subsection (1) above “liable in the United Kingdom ” means liable under the criminal or civil law of any part of the United Kingdom.

Which means, in effect, if the UK Home Secretary (“M”) signs off on a spy murdering someone, they can’t be charged with a crime in the UK.

Bond is actually more suited to a much more interesting and relevant unit in the UK Special Forces, apparently known colloquially as “The Increment” or “E Squadron”, who were caught on the ground in Libya several years ago. Allegedly derived from the Revolutionary Warfare Wing (RWW) of the Special Air Service (22 SAS) and Special Boat Service (SBS), these cream of these chaps are hand-picked by MI6 for fun adventures in foreign lands, like assassinating leaders of rogue states, and extraordinary rendition.

In fact, the real life units of the British security services (e.g. Group 13, Force Research Unit) make for much more, erm, interesting, reading than anything presented in a Bond film.

When we put the picture together, it’s not so much of a radical diversion from the actual Fleming character — it’s someone else. It’s not James Bond at all.

The real James Bond:

- Cruel

- Dull & unlikeable

- Racist, homophobic Naval Commander

- A chain-smoking (70/day) alcoholic who enjoys amphetamines

- A compulsive gambler

- Physically scarred

- A comma-shaped curl of black hair over his forehead

In essence, a sociopath in a suit: a totally 2-dimensional character deliberately designed that way to enable the story to be told through the events and supporting characters themselves.

According to Umberto Eco in “Narrative Structures in Fleming”, Fleming then used nine plot elements to structure every one of his James Bond novels, which can be generally summarised — in terms of a template-, as follows:

“Bond is sent to a given place to avert a ‘science-fiction’ plan by a monstrous individual of uncertain origin and definitely not English who, making use of his organizational or productive activity, not only earns money but [also] helps the cause of the enemies of the West. In facing this monstrous being, Bond meets a woman who is dominated by him and frees her from her past, establishing with her an erotic relationship interrupted by capture by the Villain and by torture. But Bond defeats the Villain, who dies horribly, and rests from his great efforts in the arms of the woman, though he is destined to lose her.”

Bond is there to enforce the prestige and Will of the Western World.

He dominates the woman, but loses her. He kills the villain with brutal cruelty. He is, in effect, the paradigm of the Noble Savage. You might say, the Aristocrat Savage. He is barely redeemable, let alone likeable.

What we have today, courtesy of the Broccolis and their comrades at Sony, is a character so wholly diluted that it, of course, negates the original appeal of the concept itself — bent round for American audiences to stomach. Today’s bond is an empathetic, internally-conflicted, non-smoking, likeable hero from a government program who had a bad childhood and is just trying to do the right thing, before he settles down with a wife.

Bond is naturally complex in the dichotomy of his savagery: an aristocrat in the evening, but a cold-blooded murderer after midnight; a beautifully-cut Tuxedo he destroys in casino brawls; a moral enigma it’s unclear as to whether is redeemable; a well-spoken, charming psychopath who schmoozes at the British Embassy in Vienna and despises Americans; a man without purpose other than his British imperialism. He’s more likely to murder his wife than give up his need for heroic danger — and to be honest, that’s a lot more interesting.

Imagine if this man did love someone once. She was apparently called Vesper Lynn. That’s some screen time you’d want to see, just to watch what effect she had on him.

It may take in $1BN for the stunts, but the cost was removing what made Bond who he is. It’s a shadow of what Fleming envisioned, and got right in the first place.