The Ancient English Right To Revolution

Britain is not a propositional abstract "project" with "values." It is an ancient nation derived from a people with ancient customs, rites, and liberties. When the call to revolution is made, it is never to change to something new, but to restore something old.

The English right of resistance against tyrannical rule stands as one of the most deeply rooted and consistently documented principles in constitutional history, predating even the Norman Conquest. This right emerges not as a revolutionary innovation, but as a fundamental aspect of English governance, woven into the fabric of custom and law across a millennium of recorded history.

Britannic people, who were 99.9% white until 1945 and share 30% of their genetics with Germans, have specific traits, many of which can be seen today in colonial cultures such as Americans, Canadians, Australians, and South Africans. In "The Radicalism of the American Revolution" (1991), historian Gordon S. Wood concisely explains what made this group unique:

Because monarchy had these implications of humiliation and dependency, the Anglo-American colonists could never be good monarchical subjects. But of course neither could their fellow Englishmen "at home" three thousand miles across the Atlantic. All Englishmen in the eighteenth century were known throughout the Western world for their insubordination, their insolence, their stubborn unwillingness to be governed. Any reputation the North American colonists had for their unruliness and contempt for authority came principally from their Englishness.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Radicalism_of_the_American_Revolution

What The Romans Observed About Brits

The Romans had complex and evolving views of the Britannic peoples over several centuries of interaction. Julius Caesar, in his "Commentarii de Bello Gallico," wrote:

"The interior portion of Britain is inhabited by those who claim, on the basis of oral tradition, to be indigenous to the island, while the maritime portion is inhabited by those who crossed over from Belgium for the purpose of plunder and making war."

He also noted their appearance:

"All the Britons dye themselves with woad, which produces a blue color, and makes their appearance in battle more terrible."

Many accounts emphasised the Britons' tribal divisions, which the Romans exploited in their conquest and governance of Britain. They noted how some tribes, like the Atrebates, became Roman allies, while others, like the Catuvellauni, fiercely resisted Roman rule.

Later Roman writers like Tacitus provided more detailed accounts, particularly in his work "Agricola." He portrayed the Britons as proud and fierce warriors who valued their independence. Through his father-in-law Agricola's experiences as governor of Britain, Tacitus described various tribes and their distinct characteristics - from the Caledonians in the north to the more "civilised" tribes in the south who had adopted some Roman customs. He gave one of the most famous characterisations through a speech he attributed to the Caledonian chief Calgacus:

"They create a desolation and call it peace." ("Ubi solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant").

The Romans saw the Britons as barbarians who needed to be civilised through Roman rule. However, they also respected certain aspects of British society and military prowess. Particularly notable was their admiration for Queen Boudica of the Iceni, despite her rebellion against Roman rule - her courage and leadership abilities were celebrated even by Roman historians.

Strabo, in his "Geographica," described the Britons' height and build:

"The men are taller than the Celti, and not so yellow-haired, although their bodies are of looser build."

He also commented on their exports:

"They produce grain, cattle, gold, silver, and iron. These things, accordingly, are exported from the island, as also skins, and slaves, and dogs that are by nature suited to the purposes of the chase."

Roman historian Cassius Dio provided an interesting description of northern Britons:

"They dwell in tents, naked and unshod, possess their women in common, and rear all their offspring. Their form of rule is democratic for the most part, and they are very fond of plundering; consequently they choose their boldest men as rulers."

An Unwritten Right Of Englishmen

The Right of Revolution in English legal and political thought developed primarily during the 17th century, though its roots trace back earlier. It doesn't technically exist in modern English law as a formal legal doctrine - the UK's system of parliamentary sovereignty, established after 1689, means Parliament is supposedly the supreme legal authority.

Early English constitutional thought, particularly during the Barons' Wars and even back to Anglo-Saxon times, recognised a communal right to resist tyrannical rule. This was expressed in documents like the Mirror of Justices and various medieval legal treatises. It wasn't tied specifically to Parliament but to the community of the realm acting through its natural leaders.

The concept emerged most clearly during the civil war period. At its core, it held if a monarch violated the fundamental laws and customs of the realm, or breached their coronation oath to rule justly and protect their subjects' rights, the people (typically represented by Parliament) had a right to resist and ultimately depose them.

This idea was notably articulated by political thinkers like Henry Parker and John Locke, though Locke's later work was more influential in America than England. The English version emphasised:

- The ancient constitution - the idea England had traditional, unwritten laws even kings must follow

- The contractual nature of monarchy - the belief kingship was based on mutual obligations between ruler and ruled

- The role of Parliament as the institutional check on royal power

The Bill of Rights 1689 was never repealed and remains technically part of UK constitutional law. This means the principles which justified the Glorious Revolution - a monarch can't rule arbitrarily or against fundamental laws - are still technically part of the constitutional framework. The Bill never explicitly states a "right of revolution" - instead, it presents the removal of James II as an "abdication" and then sets out limits on royal power. This deliberate legal fiction helped establish the principle while maintaining institutional stability.

"Whereas the late King James the Second, by the assistance of divers evil counsellors, judges and ministers employed by him, did endeavour to subvert and extirpate the Protestant religion and the laws and liberties of this kingdom...

By assuming and exercising a power of dispensing with and suspending of laws and the execution of laws without consent of Parliament;

...And whereas the said late King James the Second having abdicated the government and the throne being thereby vacant..."

The document then declares:

"All which are utterly and directly contrary to the known laws and statutes and freedom of this realm."

And establishes:

"The pretended power of suspending the laws or the execution of laws by regal authority without consent of Parliament is illegal...

The pretended power of dispensing with laws or the execution of laws by regal authority, as it hath been assumed and exercised of late is illegal..."

Legal theorists have debated this, and argue the right of resistance remains latent in English constitutional law as a fundamental principle even Parliament can't extinguish, similar to how Parliament can't bind its successors. Others contend parliamentary sovereignty is now absolute and has completely absorbed and replaced any independent right of resistance. The courts have generally avoided ruling directly on this question, treating it as a political rather than legal matter, so the theoretical question of whether an extra-parliamentary right of resistance still exists remains unresolved in English law.

Anglo Saxons, Wessex, & Witenagemot

The deposition of King Sigeberht of Wessex in 755 AD stands as the first clearly documented exercise of constitutional resistance in English history. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the Witenagemot (the Witan) met at Hamtun (modern Southampton) to formally consider the king's transgressions. The charges laid against him were specific - he had committed "unrighteous deeds" (unryhtum dædum) and acted against "right law" (riht lagu). The West Saxon nobles, acting through the Witenagemot, not only removed him but replaced him with Cynewulf through a formal procedure, establishing a crucial precedent for constitutional action.

The removal of Alcred of Northumbria in 774, forced to flee "by the counsel and consent of his own people," further reinforced this principle. The case of Ethelred II's removal and subsequent restoration in 1013/1014 demonstrated even restoration required Witan approval. The succession disputes of 975 between Edward and Æthelred showed the Witan's decisive role in determining legitimate rule.

The Witenagemot itself was a sophisticated institution which embodied early English constitutionalism. Its membership comprised ealdormen who governed regions, thegns from the landed nobility, senior clergy including bishops and abbots, royal officials, and sometimes representatives from major towns. This body wielded substantial powers, from electing and deposing kings to approving law codes, consenting to taxation, approving major land grants, and making decisions of war and peace.

Anglo-Saxon kingship operated within a complex theological-legal framework. The king's authority derived from coronation, yet came with explicit contractual obligations to rule justly. The coronation oath, preserved in various forms, bound kings to specific duties: defending the church, maintaining justice, suppressing wrong-doing, and protecting the people's rights. This created a clear constitutional basis for removal if these sworn obligations were broken. Felix Liebermann's comprehensive analysis of pre-Conquest legal codes demonstrates this understanding remained consistent across different kingdoms and periods.

The documentary evidence supporting this constitutional arrangement extends beyond the Chronicle. The "Fonthill Letter" demonstrates the Witan's judicial authority over kings, while numerous land charters required Witan approval for validity. The law codes of kings like Alfred and Edgar show how royal power was consistently limited by counsel. Church documents describing coronation ceremonies and their obligations provide additional evidence of these constitutional constraints.

The Norman Conquest of 1066 actually reinforced rather than displaced these constitutional principles. William I found it necessary to promise upholding "the law of King Edward" (referring to Edward the Confessor), acknowledging the binding nature of Anglo-Saxon constitutional custom. This acknowledgment by a conquering power demonstrates how deeply rooted these principles were in English governance - even foreign conquerors had to recognise them to establish legitimate rule.

This Anglo-Saxon foundation established enduring principles which would shape all subsequent English constitutional development. Royal power was understood as conditional rather than absolute. There existed an institutional mechanism for removing unjust rulers through collective noble and ecclesiastical consent. Such removal had to be justified by specific breaches of duty, and any replacement required formal approval through established procedures.

Coronation Charters & The Realm

The coronation charter of Henry I in 1100 AD represents one of the most significant documents in English constitutional history. Upon ascending to the throne, Henry faced a crisis of legitimacy - his older brother William Rufus had died in suspicious circumstances, and his elder brother Robert still lived. The charter he issued wasn't merely a collection of promises but a formal recognition of constitutional principles bound royal power. Henry explicitly acknowledged his authority derived from both divine right and the consent of the realm's magnates, establishing a dual foundation for royal authority which would shape English kingship for centuries.

The Charter's specific provisions illuminated how Anglo-Saxon principles had survived and evolved under Norman rule. Henry promised to end the abusive practices of his predecessor William Rufus, particularly in matters of feudal dues, church rights, and judicial proceedings. Crucially, these weren't presented as new concessions but as restorations of ancient rights - "the law of Edward the Confessor with those improvements which my father made with the consent of his barons." This explicit link to pre-Conquest law demonstrated the remarkable continuity in English constitutional thought.

The concept of the "community of the realm" emerged with particular force during Stephen's reign (1135-1154), a period that tested and ultimately strengthened English constitutional principles. The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon provides vivid detail of how Stephen's failure to maintain peace and justice led to resistance from both church and nobility. What makes this period particularly significant is how the resistance was framed - not as mere opposition to an unpopular king, but as a constitutional response to the breach of coronation obligations.

The term "community of the realm" (communitas regni) began to appear with increasing frequency in contemporary documents, suggesting a sophisticated understanding the kingdom was more than just the king's personal property. The chronicler William of Malmesbury records how both sides in the civil war appealed to this concept, demonstrating its central importance in political thought. Stephen's opponents justified their resistance by arguing he had failed the community of the realm, while his supporters claimed to defend it against chaos.

This period also saw the development of more formal mechanisms for expressing constitutional grievances. The church, led by figures like Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury, began articulating clearer theories about the limits of royal power. The Treaty of Winchester (1153), which ended the "anarchy" of the civil war, represents an early example of a negotiated settlement between crown and subjects.

The practice of issuing coronation charters continued throughout this period, with each new monarch effectively entering into a contract with the realm.

Stephen's own charter of 1136 expanded on Henry I's precedent, showing how these documents evolved to address current grievances while maintaining constitutional continuity. This practice helped establish the principle royal power was inherently limited and conditional upon proper governance. The idea resistance to royal misrule could be legitimate and even necessary became firmly established in English political thought, supported by both practical precedent and theoretical justification.

Magna Carta Libertatum: the Great Charter Of Freedoms

The Barons' War against King John marked a watershed moment in English constitutional history, transforming abstract principles of resistance into concrete legal mechanisms.

The immediate causes of the conflict stemmed from John's increasingly arbitrary rule - excessive taxation, abuse of feudal rights, interference with church affairs, and the loss of Normandy had created widespread discontent among the nobility. Yet what began as traditional baronial resistance evolved into something far more significant: the first systematic attempt to create a legal framework for limiting royal power.

The negotiations at Runnymede in June 1215 produced a document which went far beyond previous coronation charters or peace treaties. Magna Carta articulated a comprehensive vision of limited monarchy, establishing specific procedures for restraining royal power. The most revolutionary aspect appeared in Clause 61, which established the council of twenty-five barons.

This council was granted explicit authority to monitor royal behaviour and, if necessary, use force to correct royal abuses. The mechanism was precisely detailed - if the king breached the charter's terms, the council could seize royal castles and lands until the breach was remedied.

Issued by King John of England in 1215, established several important rights and legal principles:

Habeas Corpus and Due Process

- No free person could be imprisoned, exiled, or punished without proper legal process

- Justice couldn't be denied, delayed, or sold

- People had the right to a fair trial by their peers

Limits on Power

- The king had to follow the same laws as everyone else

- The monarch couldn't levy taxes without approval from a council of nobles

- Royal officials couldn't take property or goods without immediate payment

- The king couldn't sell, deny, or delay justice

Rights of the Church

- The English church was guaranteed freedom from royal interference

- The right to free election of church officials was protected

Economic Rights

- Standardised weights and measures were established throughout England

- London and other cities were granted the right to collect their own customs duties

- Merchants were given the right to travel freely for trade

While many of these rights initially only applied to nobles ("free men"), the Magna Carta established crucial legal precedents which eventually evolved into broader civil rights and constitutional principles. It became a foundational document for English common law and influenced later constitutional documents, including the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights.

The significance of Clause 61 cannot be overstated. For the first time, resistance to royal tyranny was not merely justified but institutionalised within the legal framework of the realm. The clause provided specific procedures for determining when resistance was legitimate and how it should be conducted. The twenty-five barons were named individuals, creating personal responsibility for constitutional enforcement. They were empowered to act with the "commune of all the land" - a phrase which recognised the broader community's role in constitutional enforcement.

Though Clause 61 was omitted from later reissues of Magna Carta, its underlying principle - resistance to royal tyranny could and should be organised through formal institutions - became a permanent feature of English constitutional thought. The very existence of this clause demonstrated even in the 13th century, English law recognised the need for formal mechanisms to check royal power.

This utter disgrace of an article by Claire Milne at "FullFact" negligently attempts to counter the historical force, spirit, and precedent of it when it was brought out again during Covid lockdowns:

The original 1215 version of Magna Carta had 63 clauses. Only four of these clauses are still relevant today, according to the parliament website. Clause 61 is not among these, as it was omitted from all subsequent versions of Magna Carta and was never incorporated into English law.

These rights are granted to the 25 barons, not to the population at large. However that is quite different again from granting the rights of rebellion to “any man”—they are only given the power to obey the barons.

"“Article 61” of Magna Carta doesn’t allow you to ignore Covid-19 regulations"

https://fullfact.org/online/did-she-die-in-vain/

The aftermath of Magna Carta proved as significant as the document itself. Though John attempted to annul it almost immediately, the Charter's principles survived his death and were reissued multiple times during Henry III's minority. Each reissue reinforced the idea royal power was limited by law and these limitations could be formally enforced. The removal of Clause 61 from later versions did not diminish this core principle - instead, it evolved into new forms of institutional restraint, particularly through the developing role of Parliament.

The theoretical framework supporting these precedents was developed through several key legal texts. Bracton's "De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae" (c.1235) explicitly stated the king was under God and the law, a principle later cited by Chief Justice Coke in opposing Stuart absolutism.

The era of Magna Carta thus represents not just a momentary victory of barons over king, but the emergence of sophisticated constitutional mechanisms for legitimate resistance. It transformed ancient principles of just rule into specific legal procedures, creating precedents which would influence English constitutional development for centuries to come.

Barons War 2.0 & de Montfort

The crisis erupted into the Second Barons' War began long before the actual outbreak of hostilities in 1264. Henry III's reign had been marked by mounting tensions over royal expenditure, foreign favourites, and papal taxation. The king's expensive foreign policies, particularly his attempt to secure the crown of Sicily for his son Edmund, stretched royal finances to breaking point. This financial crisis coincided with a series of bad harvests and growing discontent among both nobility and emerging urban classes, creating conditions for constitutional reform.

The Provisions of Oxford in 1258 marked the first systematic attempt to create a permanent framework for controlling royal power. The document established a council of fifteen members to supervise royal government, required regular parliaments three times a year, and created a complex system of administrative oversight. Through these provisions, the barons sought to institutionalize the principle royal government should be subject to regular scrutiny and control by the political community. The subsequent Provisions of Westminster in 1259 extended these reforms into local government and judicial administration, creating a comprehensive program of constitutional reform.

Simon de Montfort's leadership transformed what might have remained a traditional baronial revolt into something more revolutionary. His parliament of 1265 included not just barons and prelates but representatives of the shires and towns, establishing a precedent for broader political representation. This expansion of political participation suggested the "community of the realm" extended beyond the great magnates to include the broader political nation. De Montfort's government, though short-lived, demonstrated effective administration was possible under baronial oversight.

The actual conduct of the war revealed the sophistication of constitutional thinking in this period. The rebels consistently justified their actions not as mere opposition to royal power, but as defense of the realm's interests against misgovernment.

The Battle of Lewes in 1264, which resulted in Henry III's capture, was followed by the establishment of a new form of government through the Mise of Lewes settlement. This document attempted to reconcile royal authority with baronial oversight, creating a constitutional framework which preserved monarchical dignity while ensuring effective constraints on royal power.

The war's end in 1267 did not mean the end of its constitutional principles. Though Henry III was restored to power, the experience had permanently altered the relationship between crown and political community. The idea royal government should be subject to regular oversight through institutional mechanisms had become firmly established. The precedents created during this period - regular parliaments, administrative oversight, and the principle resistance to misgovernment could be institutionalised - would influence constitutional development for centuries to come.

The Mirror of Justices (late 13th century) articulated a comprehensive theory of communal resistance based on ancient custom.

Perhaps most significantly, the Second Barons' War demonstrated constitutional resistance could be sophisticated and constructive rather than merely destructive. The rebels had created new institutional forms and administrative procedures that would outlive their immediate political defeat. The principle that even a crowned and anointed king could be subject to constitutional constraints had been established not just in theory but in practice.

A Century Of Constitutional Crises

The deposition of Edward II in 1327 marked a watershed moment in English constitutional history, establishing crucial precedents for future resistance to royal misrule. The process began when Queen Isabella and Roger Mortimer invaded England with a small force in 1326, but what could have been merely another baronial revolt was transformed into a constitutional proceeding through careful attention to legal form. The articles of deposition, preserved in detail in the Chronicon de Lanercost, methodically built a case against Edward based on his violation of coronation obligations. The charges emphasised his breach of sacred duties: failing to listen to good counsel, losing Scotland through incompetence, allowing favourites to oppress the people, and failing to administer justice properly.

What made Edward II's deposition particularly significant was its attention to constitutional procedure. Parliament was convened to consider the articles, and Edward's son was present to ensure continuity of royal authority. The proceedings established the coronation oath created binding obligations, not merely ceremonial promises. The young Edward III's acceptance of the crown came with explicit recognition his father's fate could befall him should he similarly fail in his duties. This created a clear constitutional principle: royal power was conditional upon fulfilling the obligations of kingship.

The Good Parliament of 1376 represented the next major development in constitutional resistance. Meeting during the final years of Edward III's reign, when the aging king's grip on power had weakened, this parliament developed new institutional mechanisms for addressing royal misgovernment. The innovation of impeachment procedures allowed parliament to target royal advisors without directly challenging royal authority. The impeachment of Lord Latimer and Richard Lyons established royal ministers could be held legally accountable for their actions, creating a mechanism for indirect control over royal policy.

The parliament's speaker, Sir Peter de la Mare, articulated a sophisticated theory of parliamentary responsibility for good governance. The commons' complaints were presented not as mere grievances but as matters affecting the whole realm's wellbeing. The parliament developed procedures for investigating financial corruption and ministerial misconduct which would become permanent features of English constitutional practice. Though many of its reforms were initially reversed, the precedents it established for parliamentary oversight of royal government proved enduring.

The constitutional crisis culminating in Richard II's deposition in 1399 brought these developments to their medieval apex. The thirty-three articles of deposition, meticulously recorded in the Rolls of Parliament, represent the most comprehensive medieval statement of constitutional principles governing kingship. The articles methodically listed Richard's violations of law and custom: arbitrary seizure of property, interference with judicial process, assertion of absolute royal power, and attempts to pack parliament with compliant supporters. Each charge was specific and documented, creating a template for future constitutional proceedings.

The constitutional significance of Richard II's removal lay in its comprehensive nature. Unlike Edward II's deposition, which focused primarily on personal failings, Richard's articles addressed fundamental questions about the nature of kingship. His claim "the laws were in his mouth" - asserting absolute royal authority - was explicitly rejected in favour of the principle king and kingdom were bound by law. The proceedings established even a king's understanding of his own powers could be judged and found wanting by the political community.

Sir John Fortescue's "In Praise of the Laws of England" (c.1470) provided the most sophisticated medieval analysis of English constitutionalism, distinguishing between absolute and limited monarchy and explicitly defending the community's right to resist tyrannical rule.

The replacement of Richard with Henry IV further developed constitutional principles. Henry's claim to the throne, though based partly on descent, was primarily justified by Richard's constitutional failures and Henry's promise to rule according to law. The articles of deposition were read publicly, establishing the community of the realm had judged Richard and found him wanting. This created a clear precedent: royal power was held conditionally, subject to fulfillment of constitutional obligations which could be objectively assessed and enforced through legal processes.

A Century Of Uneasy Medieval Peace

Henry VII's ascension through conquest and parliamentary approval, rather than pure hereditary right, reinforced the principle royal authority required broader political consent. Throughout the Tudor period, despite their apparent strength, monarchs consistently worked through Parliament to achieve their aims. Henry VIII's use of Parliament for the Reformation demonstrated both the power and limitations of royal authority - even at his most absolutist, he felt compelled to seek parliamentary sanction.

The succession crises under Henry VIII led to multiple Parliamentary acts determining the succession, establishing Parliament's role in constitutional matters. The deposition of Edward VI's Protestant protector Somerset in 1549 and the complex succession arrangements around Lady Jane Grey (1553) demonstrated even Tudor monarchs were bound by constitutional constraints.

Elizabeth I's reign saw significant constitutional tensions, particularly over monopolies and religious settlement. The Golden Speech of 1601 explicitly acknowledged royal power was exercised for the public good, not personal privilege. The parliaments of the 1590s increasingly asserted their right to discuss matters of state, despite Elizabeth's attempts to restrict such debates.

James I's reign brought immediate constitutional tensions. His theory of divine right monarchy, expressed in "The True Law of Free Monarchies" (1598) and his "divine right" speech to Parliament in 1610, directly challenged English constitutional traditions. Parliament's response in the Form of Apology and Satisfaction (1604) explicitly defended ancient constitutional rights against royal encroachment.

Breakdown: Civil Wars, Killing Charles, The Republic & The Bill of Rights

Charles I's attempt to rule without Parliament created unprecedented constitutional tensions. He employed various extra-parliamentary revenue-raising schemes: Ship Money (traditionally only levied on coastal areas) was extended inland; forest laws were revived; knighthood fees were demanded. The Ship Money case of John Hampden (1637) became a constitutional landmark - though Hampden lost, the close verdict (7-5) revealed deep judicial doubts about royal power to tax without parliamentary consent.

The Scottish Bishops' Wars forced Charles to recall Parliament. The Short Parliament (April-May 1640) refused to grant money without addressing grievances and was dissolved. The Long Parliament, convened in November 1640, passed radical reforms: the Triennial Act required regular parliaments; the Act Against Dissolving Parliament prevented its dissolution without consent; the Star Chamber was abolished. Strafford's execution and the Grand Remonstrance of 1641 marked escalating tensions.

The outbreak of civil war transformed constitutional debate into armed conflict. Parliament's victory led to unprecedented constitutional innovations: the trial and execution of Charles I (1649), abolition of monarchy, and establishment of a commonwealth republic. The Rump Parliament, Pride's Purge, Cromwell's Protectorate, and various written constitutions (Instrument of Government 1653, Humble Petition and Advice 1657) represented radical experiments in government.

Charles II's restoration brought attempts to reconstruct traditional monarchy while preserving parliamentary power:

- The Cavalier Parliament (1661-1679)

- The Test Acts restricting Catholics

- The Exclusion Crisis (1678-1681) over Catholic succession

- Development of proto-political parties (Whigs and Tories)

The decisive break came with James II's reign (1685-1688). His attempts to promote Catholicism and assert dispensing power over laws led to the Glorious Revolution. The invitation to William of Orange, James's flight, and the constitutional settlement of 1688-89 established new principles:

- Parliamentary sovereignty

- Protestant succession

- Regular parliaments

- Limited monarchy

The British Bill of Rights (1689) is a foundational document in British constitutional history. Its key provisions include the establishment of Parliamentary sovereignty, limiting the monarch's power by requiring Parliamentary consent for laws, taxes, and maintaining a standing army in peacetime.

Protection of individual rights including:

- Free elections of Parliament members

- Freedom of speech and debate in Parliament

- Protection from excessive bail and "cruel and unusual punishments"

- The right to petition the monarch without fear of retribution

- Protection from fines and forfeitures without trial

- The right of Protestants to bear arms for self-defense (within the law)

The document also:

- Prohibited the monarch from interfering with the law

- Required regular Parliaments to be held

- Established the monarch cannot be Catholic or marry a Catholic

- Reinforced the independence of the judiciary

This Bill of Rights remains an important part of the UK's uncodified constitution today, though some provisions have been modified or superseded by later laws. It influenced later rights documents, including the US Bill of Rights.

The Act of Settlement 1701 further secured Protestant succession and judicial independence. This period established the fundamental principles of modern British constitutionalism: parliamentary sovereignty, rule of law, and constitutional monarchy.

The settlement's genius lay in preserving traditional forms while fundamentally altering power relationships. It avoided both absolute monarchy and republican revolution, creating instead a system of balanced constitution which would influence democratic development worldwide.

The Englishmen of British North America

The Declaration of Independence, far from being a purely radical document, actually follows the traditional English pattern of justified resistance to tyranny.

"He has refused his Assent to Laws..."

"He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws..."

"He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly..."

This format precisely mirrors English constitutional documents like the Declaration of Rights of 1689, listing specific violations of established rights rather than proclaiming new abstract principles. The Americans were essentially following the English template for justified revolution - documenting concrete breaches of traditional liberties necessitated resistance.

From the Anglo-Saxon Witenagemot through the Magna Carta, the Civil War, and the Glorious Revolution, English political culture had developed a sophisticated framework for justified resistance to authority which saw it not as rebellion but as the defense of traditional rights.

Jefferson wrote:

"All experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed,"

He was expressing a fundamentally English conservative revolutionary principle - resistance should come only after long suffering and should preserve rather than destroy established institutions.

The Americans' "unruliness" was thus not a rejection of their English heritage but its fullest expression. They were applying the ancient English right of resistance to their particular circumstances, just as their ancestors had done repeatedly throughout English history.

Rejection Of The Revolution In France

Ever England's disagreeable brother, similar events were happening in France as were happening in the American colonies. Edmund Burke, the "Father of Conservatism", defender of the Americans, and England's later Prime Minister, was fundamentally opposed to the French ideas of burning everything down and starting from Year Zero.

In the 1780s, France was facing severe financial problems, largely due to its involvement in the American Revolution and years of expensive wars. The monarchy, led by Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, lived in luxury at Versailles while ordinary people struggled with high taxes and food shortages. Meanwhile, the Enlightenment had spread ideas about individual rights, democracy, and questioning traditional authority.

French society was divided into three estates: the First Estate (clergy), Second Estate (nobility), and Third Estate (everyone else - about 98% of the population). The first two estates paid almost no taxes despite their wealth, while the third estate bore most of the tax burden.

The revolution began in earnest when the Third Estate declared itself the National Assembly in June 1789, taking an oath not to disperse until France had a constitution (the Tennis Court Oath). On July 14, 1789, Parisians stormed the Bastille prison, which became a symbolic moment of revolutionary uprising.

The Assembly abolished feudal privileges and issued the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, establishing basic rights and principles of the new republic. However, the revolution soon became more radical. When Louis XVI attempted to flee France in 1791, he was captured and eventually put on trial. Both he and Marie Antoinette were executed by guillotine in 1793.

The revolution then entered its most violent phase, known as the Reign of Terror (1793-1794), led by Maximilien Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety. Thousands were executed as suspected enemies of the revolution, including many revolutionary leaders themselves. Robespierre himself was eventually overthrown and executed, ending the Terror.

In 1790, Burke published his famous book "Reflections on the Revolution in France" which was extraordinarily influential on the English mind. For England, Burke saw legitimate revolution as fundamentally conservative - aimed at preserving ancient rights and liberties rather than creating new ones. His interpretation of the Glorious Revolution contrast with events in France, viewing 1688 as a necessary restoration of traditional English liberties rather than a radical break with the past.

Burke believed England possessed what he called "prescriptive rights" - liberties established through long usage and custom. In his view, revolution in England could only be justified when it aimed to protect these ancient constitutional rights against innovation or tyranny. He articulated this in his speech "On the Acts of Uniformity" (1772), where he emphasised English liberty was an inheritance, not an abstract right.

The key elements Burke saw as justifying revolution in England were:

- Clear violation of established constitutional principles

- Exhaustion of all regular means of redress

- Action by legitimate representatives of the political community

- Intent to restore rather than remake the constitutional order

However, Burke was explicit such revolution should be rare and undertaken only in extreme circumstances. In "An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs" (1791), he argued while the right of revolution existed in English constitutional theory, it should be exercised with great caution and only when absolutely necessary to preserve fundamental liberties.

Chartists & Working Class People Power

The Chartist Movement represents one of the most significant developments in English constitutional resistance, marking the first time mass working-class political action was organised around specific constitutional demands. Beginning in 1838 with the publication of the People's Charter, the movement emerged from the disappointment of the 1832 Reform Act, which had extended voting rights to the middle class but excluded working people.

The Charter's demands were rooted in English constitutional history but represented a radical reinterpretation of traditional rights. The Chartists argued universal male suffrage was not a new right but the restoration of ancient Saxon liberties lost under Norman rule and subsequent corruptions. This connection to historical rights was articulated particularly by Feargus O'Connor and William Lovett, who drew direct lines from Magna Carta to their contemporary demands.

The movement's organisational structure was sophisticated and unprecedented. The National Charter Association, formed in 1840, became Britain's first national working-class political organization. Local Chartist groups established their own newspapers, meeting halls, and educational institutions. The Northern Star, edited by Feargus O'Connor, achieved a circulation which rivaled established newspapers, creating a parallel working-class public sphere.

The presentation of the three great petitions to Parliament (1839, 1842, and 1848) demonstrated both the movement's mass support and its commitment to constitutional methods. The 1842 petition, with over three million signatures, represented an extraordinary feat of political organisation. The rejection of these petitions led to increasing tension between "moral force" Chartists who advocated peaceful pressure and "physical force" Chartists who argued for more direct action.

The 1842 General Strike, or "Plug Plot," marked a crucial moment when Chartist constitutional demands merged with industrial action. Workers across northern England and the Midlands struck for both political rights and economic demands, creating a new form of political-industrial resistance. This combination of political and economic demands would influence all subsequent British radical movements.

The movement's relationship with middle-class radicals was complex. While some middle-class reformers supported universal suffrage, many backed away when Chartism became associated with working-class militancy. The Complete Suffrage Union, led by Joseph Sturge, attempted to bridge this divide but ultimately failed to unite middle and working-class reformers.

Female Chartist associations organised independently and often took more militant positions than their male counterparts. Women like Elizabeth Neesom argued political rights were necessary to protect working women's economic interests.

The movement's decline after 1848 did not mean failure. Most Chartist demands were eventually achieved, though over a much longer timeframe than activists had hoped. The movement established important precedents: mass peaceful protest, working-class political organisation, and the connection between political and economic rights. It demonstrated constitutional resistance could be both radical and disciplined, violent and lawful.

Chartism's legacy profoundly influenced subsequent British political development. The movement proved mass political organisation was possible and working-class people could articulate sophisticated constitutional arguments. Its combination of radical demands with traditional constitutional principles created a distinctively English form of revolutionary politics which influenced later labour and socialist movements.

The Chartist interpretation of English constitutional history - seeing it as a story of lost rights to be reclaimed rather than merely preserved - represented a crucial development in revolutionary thinking. This framework would influence successive generations of radicals who sought to combine fundamental change with appeals to historical legitimacy. Would you like me to explore any particular aspect of the movement in more detail?

Empire, World Wars, & Whacky Loons

The core conservative revolutionary tradition in English constitutional thought was built through several key thinkers. Henry Parker's 1642 tract "Observations upon some of His Majesties late Answers and Expresses" established the fundamental principle resistance to royal power could be conservative in nature, aimed at preserving rather than overthrowing traditional liberties. Sir Edward Coke's "Institutes of the Laws of England" developed this further, arguing the common law itself contained the principles of justified resistance, while Blackstone's "Commentaries on the Laws of England" solidified the view of the Glorious Revolution as constitutional restoration rather than radical change.

The Victorian era marked a crucial transition. While thinkers like Sir Henry Maine in "Ancient Law" (1861) continued to emphasise institutional continuity, new radical voices emerged. William Morris and John Ruskin began to articulate a different vision of socialist revolutionary change, one which still drew on English traditions but pointed toward more fundamental social transformation. Morris's "How We Live and How We Might Live" (1884) particularly demonstrated how traditional English constitutional thinking could be adapted to more radical ends.

Under the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst, the Suffragette movement combined militant direct action with sophisticated constitutional arguments about ancient English liberties. The suffragettes' window-breaking campaigns, hunger strikes, and mass demonstrations created a new template for revolutionary action while their theoretical writings connected women's rights to traditional English constitutional principles about representation and consent to governance.

The General Strike of 1926 introduced class-based revolutionary thinking into English constitutional discussion. The miners' leaders, particularly A.J. Cook and Herbert Smith, articulated a theory of industrial action as constitutional resistance, arguing workers' rights were as fundamental to English liberty as parliamentary representation. The Trade Union Congress's handling of the strike demonstrated how mass industrial action could be framed within traditional constitutional principles.

The post-war period saw the emergence of the New Left, with communist figures like Raymond Williams, Stuart Hall, and Perry Anderson attempting to reconcile English constitutional traditions with continental revolutionary theory. Their journals, particularly the New Left Review, developed sophisticated analyses of how English institutional continuity could accommodate radical social change. This intellectual project reached its height in E.P. Thompson's monumental "The Making of the English Working Class" (1963), which reinterpreted English radical traditions through a Marxist worldview while maintaining their distinctively English character.

John Major & New Labour Usurp Parliamentary Sovereignty

The traditional doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty, as articulated by Dicey, has been fundamentally altered by three major constitutional developments.

The European Union (1973-2020) introduced a completely new constitutional order. The European Communities Act 1972 meant EU law had primacy over UK law. This was confirmed in Factortame (1990), where the House of Lords acknowledged UK courts could disapply Acts of Parliament which conflicted with EU law - a direct challenge to parliamentary sovereignty. Even after Brexit, the theoretical framework this created has permanently altered understanding of constitutional supremacy in English law.

The Human Rights Act 1998 and membership in the European Convention on Human Rights created another external constraint. While Parliament can technically legislate contrary to the ECHR, Section 3 of the HRA requires courts to interpret all legislation as compatible with Convention rights where possible. Section 4 allows courts to issue "declarations of incompatibility" when legislation conflicts with human rights. Though Parliament isn't legally bound to change such laws, the political pressure to comply creates a practical limitation on sovereignty.

The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 and creation of the Supreme Court marked another significant shift. While technically the Supreme Court remains subordinate to Parliament, its recent judgments have demonstrated increasing willingness to review parliamentary action. The Miller cases (2017 and 2019) and the Prorogation case showed the court asserting power to rule on fundamental constitutional matters. The court effectively created new constitutional principles limiting executive power, demonstrating parliamentary sovereignty is now subject to judicial oversight of constitutional boundaries.

Together, these changes have created a "bi-polar sovereignty" where power is effectively shared between Parliament and the courts, with external rights frameworks providing additional constraints. While Parliament retains theoretical absolute sovereignty, in practice it operates within a complex web of legal, constitutional, and political constraints unrecognisable to earlier constitutional theorists.

Understanding The English Attitude to Revolution: Restoration

The English conception of revolution is uniquely conservative and institutional - not in the modern political sense, but in literally seeking to "conserve" ancient rights and liberties. Unlike the French or American revolutionary traditions which seek to create new rights based on abstract principles, the English tradition consistently frames resistance as restoration of ancient liberties which have been encroached upon.

This creates a distinctive pattern where even radical change is justified through appeals to historical precedent. The Magna Carta, the Civil War, the Glorious Revolution, and even the Chartists all claimed to be restoring lost rights rather than creating new ones. This pattern continues today in arguments about constitutional reform.

Fundamental Texts for Understanding the English Revolutionary Mind:

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (particularly regarding the Witenagemot and removal of kings)

- Bracton's "On the Laws and Customs of England" (c.1235)

- The Mirror of Justices (late 13th century)

- Magna Carta (1215) - particularly Clause 61

- Sir Edward Coke's Institutes of the Laws of England

- The Bill of Rights 1689

- Edmund Burke's "Reflections on the Revolution in France"

- E.P. Thompson's "The Making of the English Working Class"

The current constitutional crisis presents an interesting paradox. Parliament's sovereignty was historically derived from its role as representative of the "community of the realm" against royal power. But if Parliament itself becomes corrupt or unrepresentative, the ancient right of resistance logically should still exist.

The argument for a latent right of revolution today would rest on several historical principles:

- The Anglo-Saxon precedent ultimate political authority rests with the community of the realm, not any particular institution.

- The medieval principle legitimate authority depends on fulfilling obligations to the community - just as kings could be deposed for failing their duties, Parliament's authority might be conditional on proper representation.

- The principle from 1688 fundamental breaches of the constitution justify resistance - if Parliament has allowed its own corruption, this might constitute such a breach.

Parliament's power ultimately derives from its historical role as representative of the community of the realm. If it fails in this role, the ancient right of resistance arguably reverts to the community itself. The creation of external constraints through the EU, ECHR, and Supreme Court suggests absolute parliamentary sovereignty was always a temporary phase rather than a permanent constitutional settlement.

This view is supported by the historical pattern of English constitutional development, where institutional authority has always been understood as conditional rather than absolute. Just as the royal prerogative was gradually constrained when it became corrupt or abusive, parliamentary power might be subject to similar limitation when it fails its constitutional purpose.

The unique English genius for revolution has been its ability to achieve fundamental change while maintaining institutional continuity and constitutional legitimacy. Any modern resistance would likely need to follow this pattern - not destroying institutions but restoring their proper constitutional function.

This reading suggests, far from being obsolete, the ancient English right of resistance might be more relevant than ever - not as a right to destroy the constitutional order, but to restore its proper function when institutional corruption has perverted it from its purpose.

The English revolutionary tradition thus provides a sophisticated framework for constitutional resistance which neither fetishises institutional forms nor descends into pure populism, but seeks to maintain the proper balance between institutional authority and popular sovereignty has characterised English constitutional development for over a millennium.

England's Disastrous Experiment With Socialism Courtesy of Three Labour Governments

The English constitutional tradition fundamentally views rights and liberties as inherited - what Burke called "an entailed inheritance derived to us from our forefathers, and to be transmitted to our posterity." This stands in direct opposition to the socialist conception of "progress" toward a hypothetical future state, unmoored from historical tradition.

Atlee's reforms exemplify this tension. While traditional English liberty was built on property rights, common law, and local custom accumulated over centuries, the nationalisation program sought to create an entirely new relationship between citizen and state. The welfare state represented not an evolution of English rights but their replacement with a continental model of state-granted positive rights. Where English liberty had grown organically from historical experience, the post-war settlement attempted to design society from abstract principles.

The nationalisation program could be viewed as a modern parallel to the Norman Conquest's transformation of property relations. English liberty transformed from negative rights (freedom from interference) to entitlements. The nationalisation of land, and of the Bank of England altered the ancient relationship between Crown, Parliament, and monetary sovereignty dating back to the Tudor period.

Wilson's period demonstrates the progressive impulse to erase historical continuity, both literally and figuratively. Brutalist architecture physically removed ancient urban landscapes, replacing organic community development with planned environments. The removal of traditional rights wasn't seen as a loss of liberty but as "progress" toward a "modern" society. This reflects a fundamental difference in worldview - where traditional constitutionalism sees wisdom accumulated in ancient practices, progressive thought often views tradition as obstacle to overcome.The unwanted restriction of firearms ownership removed rights dating back to the Bill of Rights 1689. The unwanted abolition of the death penalty, while humanitarian, altered judicial powers established since Anglo-Saxon times.

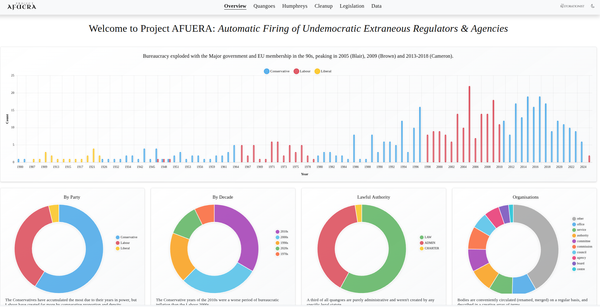

The Blair/Brown "young country" concept explicitly rejected the value of historical continuity. The creation of unelected agencies (quangos) echoes complaints against Tudor and Stuart "evil counsellors." The devolution of powers fragmented what Blackstone called "the unity of the realm." Devolution wasn't aimed at preserving historical nations but creating new administrative units (councils or "soviets"). The Equality Act substituted abstract rights theories for common law traditions developed through centuries of practical experience. Parliament has handed over its powers to bureaucrats of modern "soviets."

This highlights a crucial distinction: English constitutional thought sees society as an organic development, with each generation adding to accumulated wisdom, while socialist progressivism envisions society as a project to be designed and implemented. The former views rights as discovered through experience and preserved through tradition; the latter sees them as invented through theory and imposed through legislation.

From this perspective, these changes represent not just policy differences but a fundamental attempt to replace England's historical constitutional character - built on precedent, custom, and accumulated rights - with an ahistorical administrative state built on abstract theory. This mirrors the difference between common law (grown through experience) and civil law (designed by theorists) traditions.

The British hate it.

When Parliament Becomes Its Own Aristocracy: The Right To Overthrow What We Have Today

The English constitutional tradition provides a robust framework for justified resistance when governing bodies breach the social contract.

The core principle begins with the Saxon Witenagemot and folkmoots - the ancient understanding legitimate authority stems from the people's consent and mutual obligation between rulers and ruled. This was codified in the Anglo-Saxon Coronation Oath, where monarchs swore to uphold "righteous laws" and serve the people's welfare. The Anglo-Saxon folkmoot tradition actually provides historical precedent for direct participation - the idea governance requires active consent and participation from the governed.

The Magna Carta (1215) established the crucial precedent no ruler stands above the law and tyrannical governance voids the bonds of loyalty. Clause 61 explicitly provided a right of resistance when rulers breach their obligations. This was reaffirmed in the Provisions of Oxford (1258), establishing even Parliament must operate within constitutional constraints.

The Declaration of Rights (1689) further crystallised governing authority is conditional upon fulfilling specific duties to the people. Parliament gained its authority by defending these rights against monarchical overreach - logically, Parliament itself cannot claim immunity from the same principles which justified its own rise to power.

The English Civil War provided precedent when governors become tyrants, they functionally abdicate their legitimate authority. As articulated by Parliamentary theorists, legitimate authority requires adherence to constitutional principles, not merely holding institutional position.

John Locke, drawing from these traditions, argued in his Second Treatise when governors breach their trust and "act contrary to their trust," power "devolves to the people, who have a right to resume their original liberty." This wasn't radical theory but a concentration of long-standing English constitutional thought.

Parliament's authority stems from its role protecting ancient rights and liberties. If Parliament itself becomes tyrannical, it breaches the very source of its legitimacy. The same principles which justified resistance to monarchical tyranny would apply - as the people never surrendered their fundamental rights, only delegated them conditionally.

Key indicators of such a breach would include:

- Systematic corruption of electoral processes

- Elimination of meaningful representation

- Concentration of power in a hereditary/self-perpetuating elite

- Violation of fundamental rights established in Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights

The English constitution's genius lies in recognising legitimate authority requires consent and constitutional behavior, not mere institutional position. When governors become tyrants, resistance becomes duty - not to destroy law, but to preserve it against those who have functionally abandoned it through their actions.

The key constitutional argument would be modern technology finally enables true return to first principles - direct participation and consent which the representative model only approximated due to practical limitations of pre-modern communication. Cryptographic voting and verification could provide stronger guarantees of electoral integrity than current systems.

Key elements of such a system might include:

- Cryptographically secure identity and voting systems, ensuring one person one vote while preserving privacy

- Deliberative forums enabled by technology but grounded in local communities

- Multi-layered decision making where local issues remain local (preserving the subsidiarity principle from medieval governance)

- Decentralised ledgers to ensure transparency and prevent manipulation

- Regular binding referenda on major issues, similar to Switzerland

- Citizen initiatives to propose legislation when reaching certain thresholds

Parliament arose as a practical compromise in an age of slow communication and limited literacy. Now technology enables direct participation at scale, the logical evolution would be toward Swiss-style direct democracy rather than reversion to monarchy.

The counter-argument favouring monarchy would be direct democracy risks mob rule without proper deliberation. However, proper technological architecture could actually enable more reasoned deliberation than current systems, with mandatory study periods, structured debate, and graduated decision making processes.

This combines ancient principles of consent with modern capabilities - essentially fulfilling the original promise of democracy which was technologically impossible before now. This better realises the ancient principle legitimate authority stems from the ongoing consent of the governed, rather than simply periodic delegation to representatives who may become detached from their constituents, such as Burke favoured.

In our times, English men and women are openly calling for revolution. Perhaps it is time we discussed what it might look like and how it might be peacefully achieved.