Story Plot Structures: How Plays, Games, And Movies (Don't) Work

A good story tells itself. If you are finding yourself stuck and attempting to force the events of a story, your story sucks. Or, you suck at telling stories. Stories with true narrative force are unstoppable. 99.9% of stories created today - even through the 36 situations - are boring in the least, total nonsense at best.

One-Eyed Typists In A World Of The Blind

Most "writers" simply can't write. They're mediocre, literal-minded hacks who have never been anywhere, never done anything, don't know anything, have a shockingly vapid moral value system, and are the least interesting company you could be burdened with. They fall in love with their own creations. There is so much crap, when something less mediocre arrives, it's heralded as genius.

The classic example of narrative force is "The Count of Monte Cristo" by Dumas: sheer, brutal, inescapable forward motion which you cannot stop or abandon until it is fulfilled. Not simply compelling, but engrossing and kidnapping. The story steals you. You have to know.

There are a volume of pretentious descriptors entertainment professionals, film critics, and social science frauds use to describe how stories "should" be: entertaining, involving, moving, inspiring, adsorbing, enjoyable, provocative, exciting, enticing, captivating, powerful, and so on.

Actors obsess over their characters' "motivation". Screenwriting "gurus" obsess over inculcating the same thing into their "students".

It inevitably descends into some cheap cliche about "saving" people.

Bullshit. Bullshit, bullshit, bullshit.

Hannibal Lecter doesn't have a "motivation", and neither does Iago. It's the inexplicable behaviour which enthralls us.

A true story is something which envelopes you. It transports you into another time and place, taking you hostage into a desperate plight inside its twists and turns. You don't "want" to know, you HAVE to know; you aren't "interested", you are OBSESSED. You are not there in your seat, you are with them in their surroundings. Nothing else in the material world is as interesting.

What NOT To Write About

Stories suck more than they rock, as it were. It's not hard to know which stories to tell: just go for a drink with friends and see which ones make them drift off to sleep. If they are reaching across the table, forcing you to stay and tell the rest instead of going to the bathroom, you're onto a winner.

However, there are some home truths you need to imbibe and ingest on an existential level:

- Nobody gives a shit about your life. Something which happened to you and your friends, or how you met your wife, are of no interest to anyone. It's the same as you pulling out the family photo album.

- Nobody wants to hear your autobiography. It's only interesting to you. If your life was interesting, someone else would be writing about it.

- Nobody is interested in your weird hobby or fantasy world. Tolkien was creating different languages before he wrote LOTR. C.S. Lewis was penning a Christian allegory.

- Nobody will believe your wish fulfillment fantasies where you are the imaginary protagonist. Heroes don't behave like you: you're an idiot on a laptop in Starbucks.

- Nobody gives a shit about your political opinion, or your "advocacy" or your "activism", or your "highlighting" of "social issues", or how the world "should" be. If you want to produce propaganda, go work in Pyongyang.

Sorry milennials, you can't write. Your Insta photos and Tik-Tok vids aren't "stories", and your self-help bookshelf, catchy "inspiration" memes, and "social justice" ideas are an embarrassment. Oh, and J.K Rowling is Gen-X.

The Plot Structure Templates

Where does it start? Generally in two places:

- Once upon a time...

- What if?

An Infamous Crime. A brutal Tragedy. A sensational Victory. A chaotic Farce. A mind-binding Invention. A romantic Sacrifice. A nerve-wracking Adventure. A costly Rescue.

Where do you find all these elements? In one single story. See if you can figure out which one. Clue: it involves an execution.

Next, you need to create a structure which takes the audience captive. Over thousands of years, several variants have emerged. A structure is a map.

Aristotle's Poetics (335 BC)

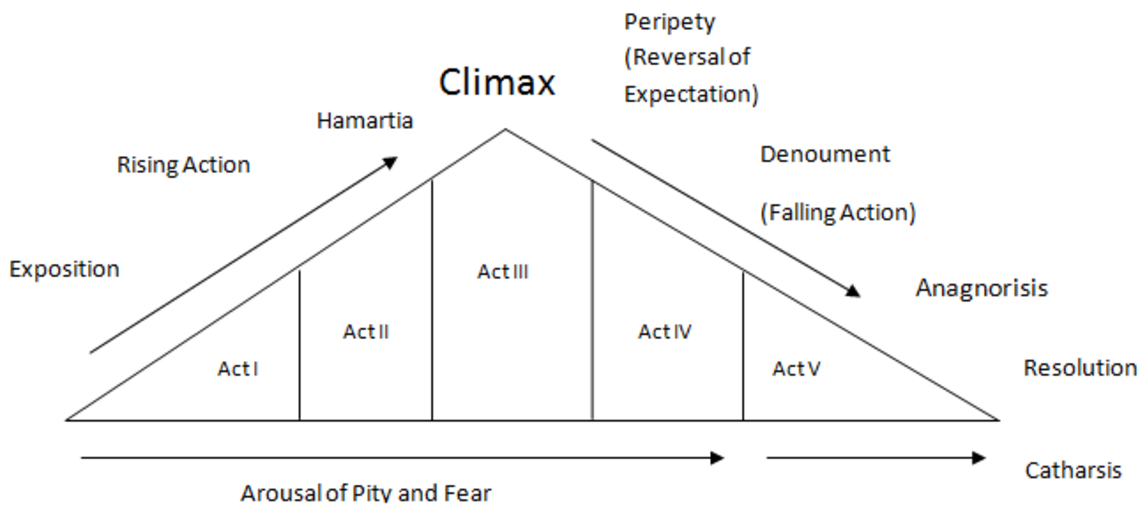

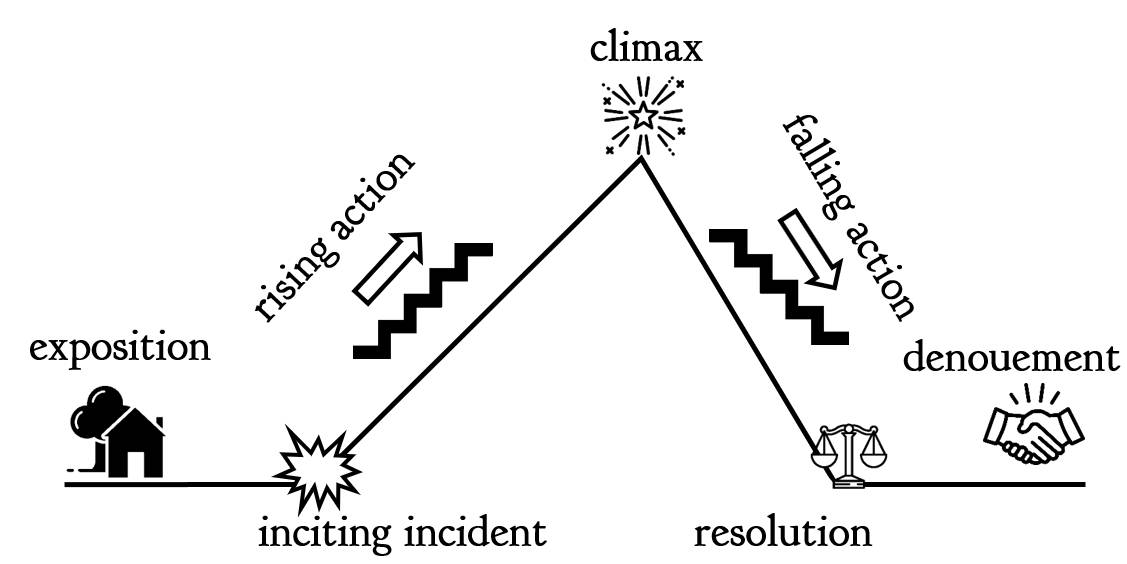

The Poetics sets out all the rules for storytelling. Aristotle makes the case to his mentor Plato the arts are as valuable as reason. His tome is an explication of how poetry works. Tragedy, as a form of imitation (mimesis) serves to arouse the emotions of pity and fear, and to effect a catharsis of these emotions. It consists of: (1) mythos, or plot, (2) character, (3) thought, (4) diction, (5) melody, and (6) spectacle. A story has a beginning, middle, and an end. They are divided by peripeteia (reversal of fortune, and anagnorisis (recognition of harmatia, or the tragic flaw).

Freytag's Five Act Pyramid (1863)

Die Technik des Dramas by German playwright and novelist Gustav Freytag claims stories should be structured into five parts: introduction, rise, climax, return/fall, and resolution. Borrowing from Aristotle, he applies the typically romantic German sense of nihilist structuralism to what was a study of beauty.

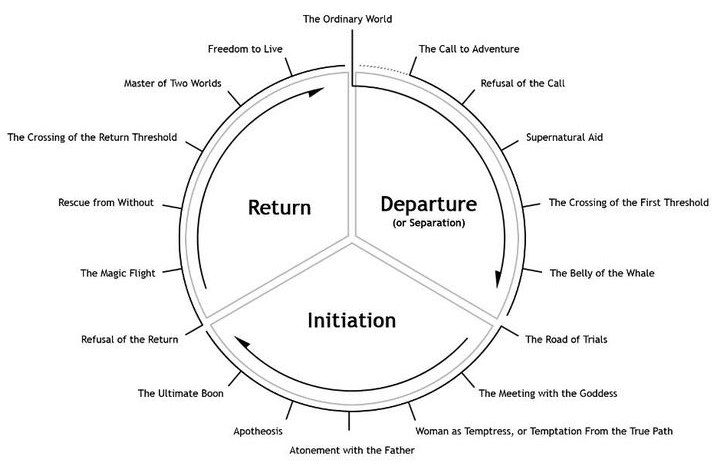

Campbell's Hero's Journey Monomyth (1949)

In a phrase, Star Wars. Joseph Campbell, obsessed with Carl Jung, published The Hero with a Thousand Faces launching even more rip-offs. His original idea was to explain religious folklore: "a hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man."

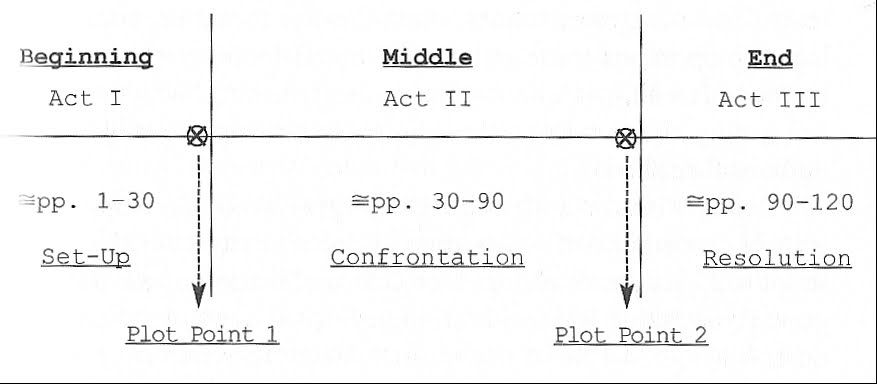

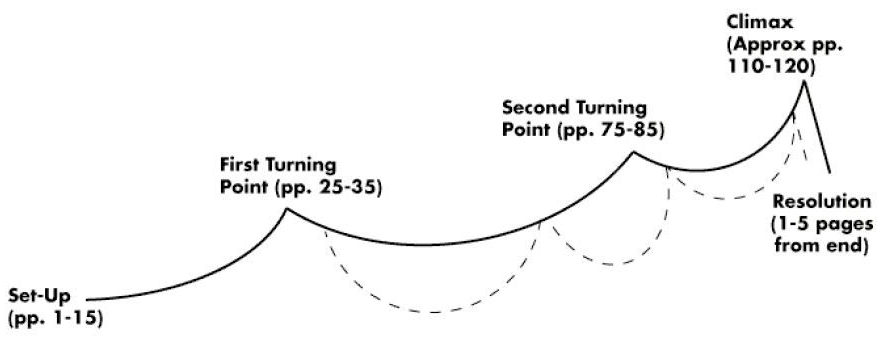

Syd Field's Three Act Paradigm (1979)

Few people of less distinction are celebrated more than Hollywood guru Syd Field, who published The Foundations of Screenwriting. It now informs almost all crappy films, everywhere. A protagonist has a "motivation" to achieve a "goal", which ends in the worst social science abstraction imaginable.

Linda Seger's Story Spine (1984)

"Feminist theology" quaker guru Seger published Making a Good Script Great at the height of the Reagan era and claims to be the most "prolific" author of the entire domain. It's more a guide to the craft, but the substance is about as useful as anything from an author who professes feminism is an answer to anything at all.

The "spine" was mentioned by a female animator in her 2012 "22 rules of storytelling" by Pixar: https://www.aerogrammestudio.com/2013/03/07/pixars-22-rules-of-storytelling/

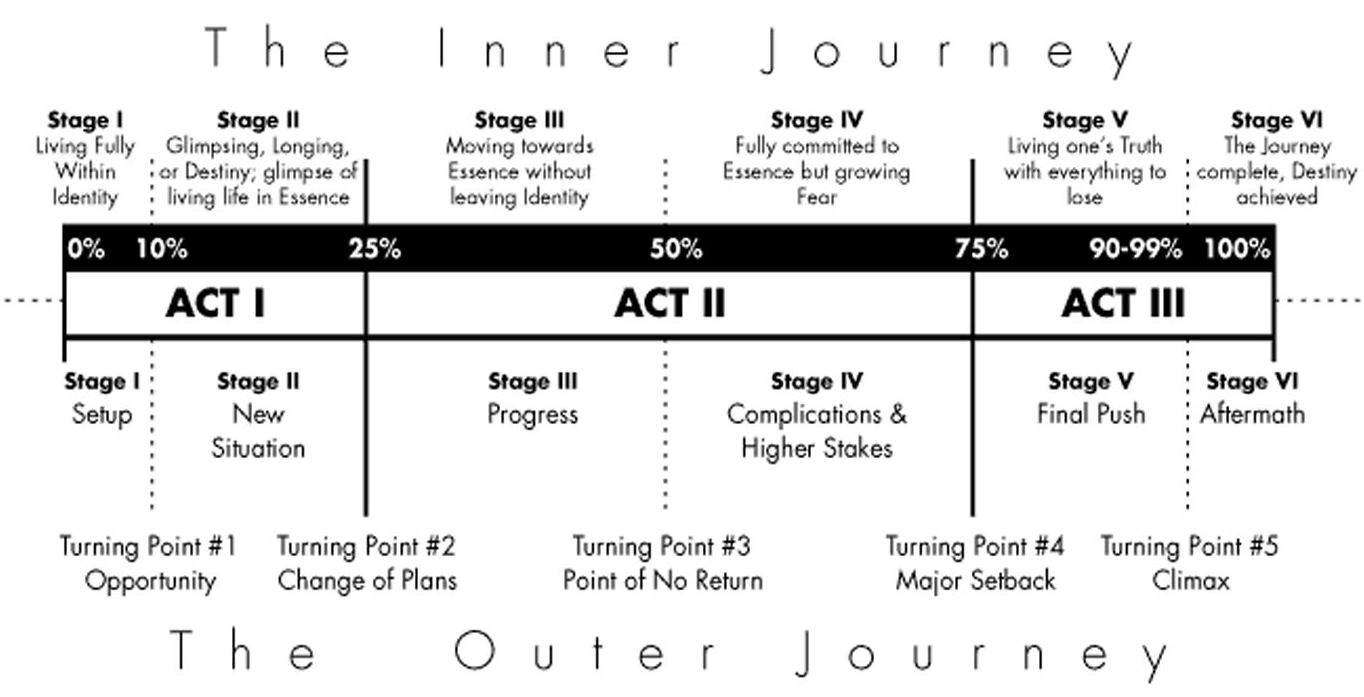

Hauge's Six Stages (1991)

Michael Hauge's Writing Screenplays That Sells doesn't really attempt to camouflage its intellectual merits and lays it out clearly - it's about soporific coaching with bad grammar that sells. His stages are more nuanced and take us more deeply into Field's bloodless bookmarks.

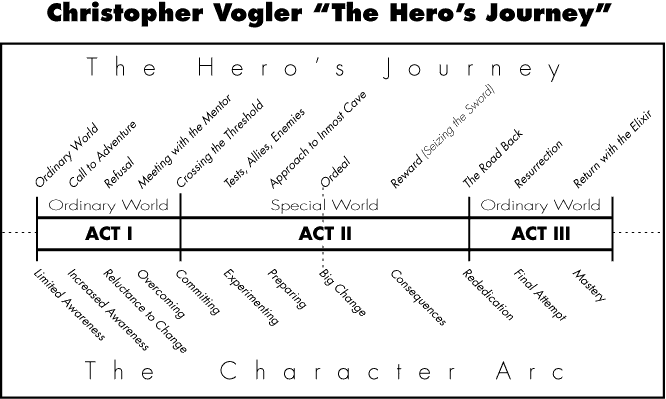

Vogler's Writer's Mythic Journey (1992)

In The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Storytellers and Screenwriters, guru Christopher Vogler made a career out of plagarising Campbell's sociology and summarising it into memos for talentless Hollywood studio execs - the people wrecking others people's work to mangle it into theirs.

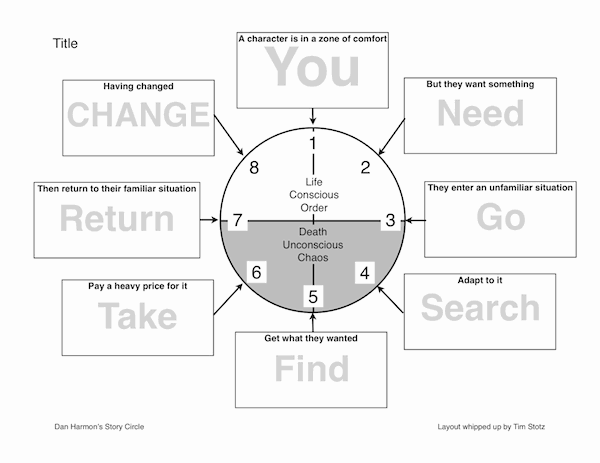

Harmon's 8-Segment Story Circle (late 90s)

In yet another plagiarism of Campbell, aspergic "anthropologist" Dan Harmon, famous for Rick and Morty, described an 8-stage "plot embryo" to help writers devise storylines he began formulating in the nineties. All you need to know about Harmon is his view on Elaine Morgan's idiotic feminist "aquatic ape theory": "a peaceful, interesting, mythical concept, and a scientific one, that maybe the origin of (humans) was kind of a fairy tale."

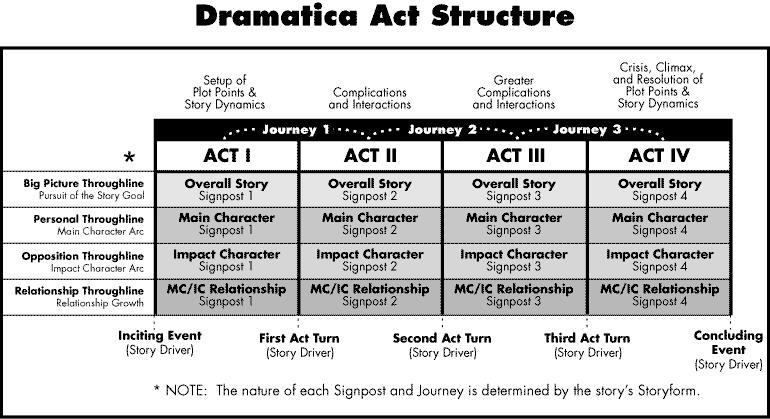

Dramatica (2004)

Probably better to file in the "WTF" category, Melanie Anne Phillips and Chris Huntley's Dramatica: A New Theory of Story reads more like a Millenarian New Age cult propaganda handbook, where they depart from all those boring historical ideas. Philips "worked as a consultant for the CIA and NSA applying her theories of narrative psychology to counter-terrorism, and currently promotes narrative analysis in fiction and the real world" and Huntley claims "Dramatica theory posits that stories are models of human psychology, specifically metaphors for the mechanisms of a mind attempting to resolve an inequity".

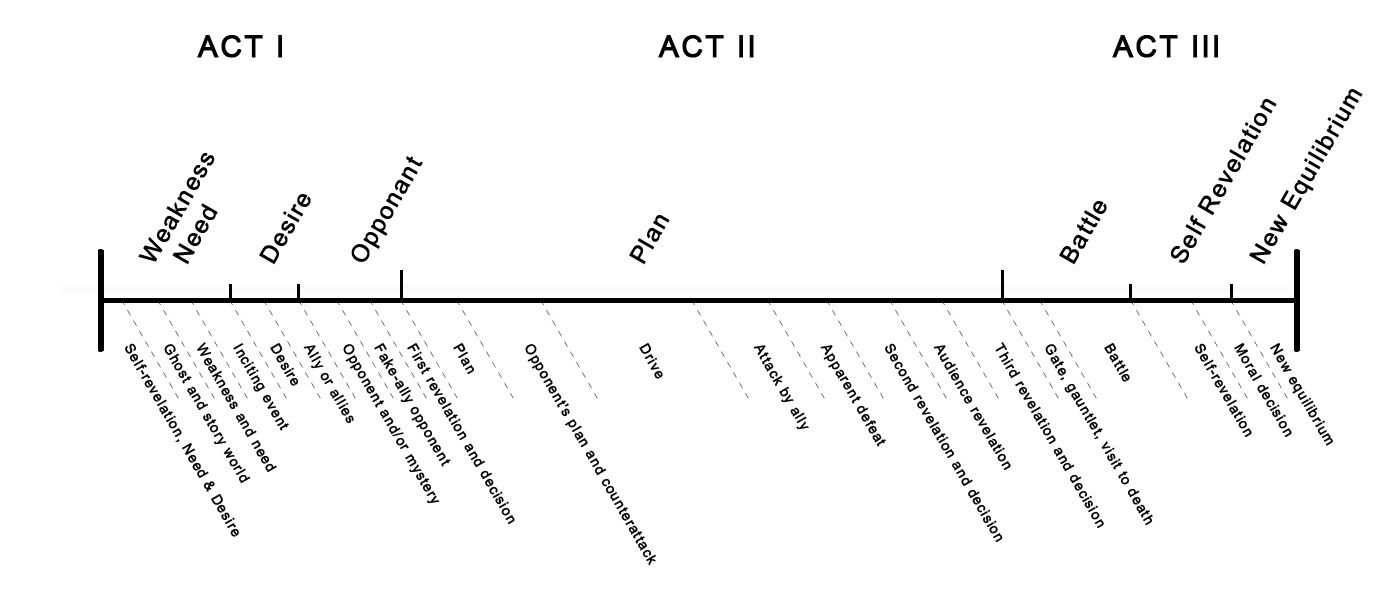

Truby's 22-Step Anatomy (2007)

John Truby is a thinking mind. His The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Storyteller is a detailed work summarising the important parts of a compelling screenplay sequenced into 22 "blocks". However, it's compounded by the prescriptive and technical nature of an producing something based on expressing beauty, and the fact he's... wait for it... another consultant.

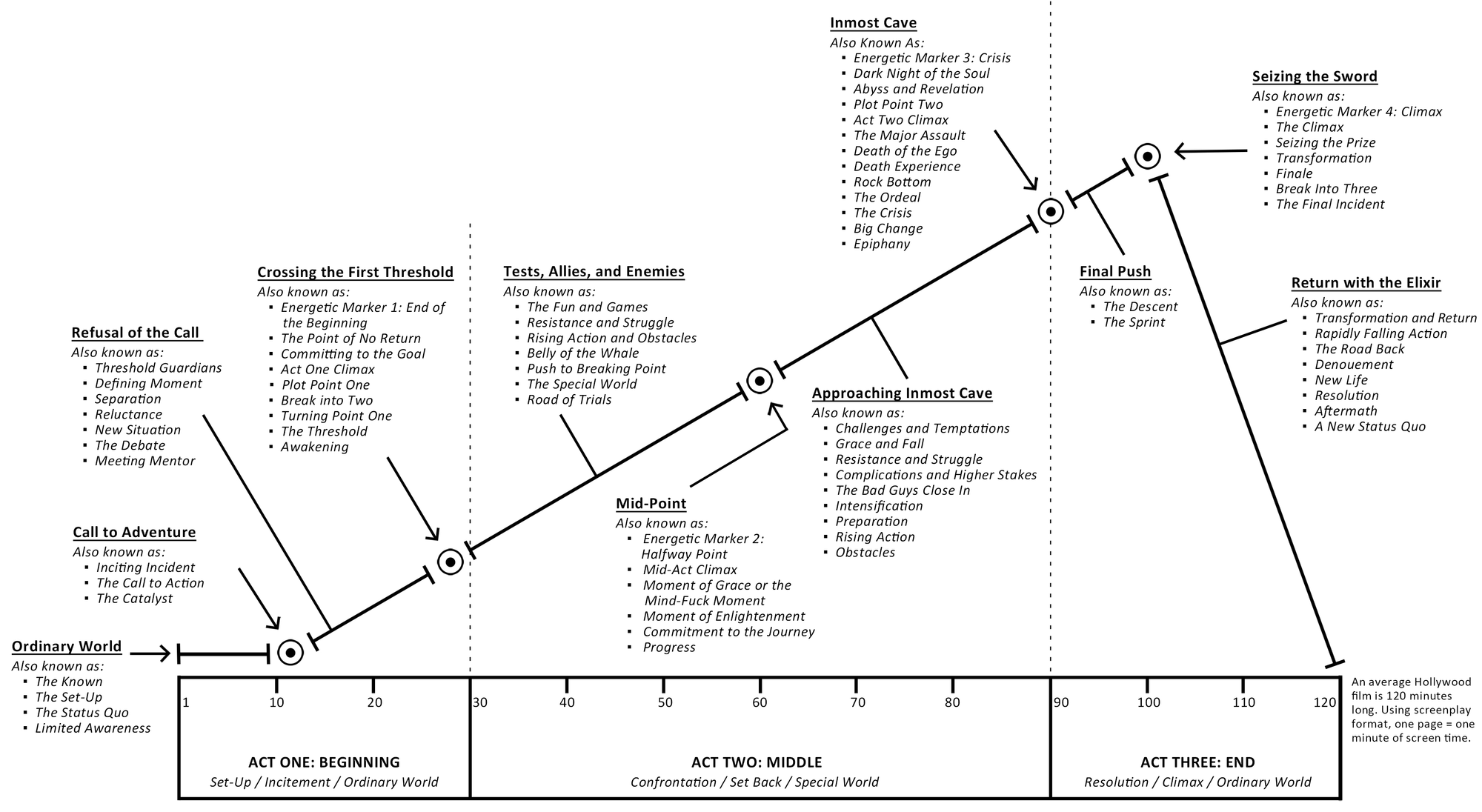

Sundberg's Arch Meta-Mountain (2013)

Although not a plot structure in itself, Ingrid Sundberg's combined "arch plot" is a great summary of the competing structures, broken down into 11 sections.

But... Nobody Knows Their Stories

Robert McKee wrote a book called "Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting," about stories, but doesn't offer a plot structure. It's a rehash of Aristotle.

Black Snyder's "Save the Cat" is a rehash of Campbell's monomyth, like Vogler, Hauge, and Harmon's. However, they expand and re-map the analysis. Whereas Snyder simply produces a blueprint for predictably terrible films.

When you actually compare most of these "gurus" or their work, it's hard to actually determine what any of them have actually contributed to storytelling other than to explain what Aristotle told Plato, or Campbell described in his sociology essays about religious folklore.

It's even harder to point to any of their published stories ordinary people know and love.

For example, Oscar Wilde wrote Dorian Gray. Ayn Rand wrote Atlas Shrugged. George Orwell wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four. Christopher Nolan wrote Inception.

These authors required structure, but didn't turn their art's servant - the layout - into its master.

Stories tell themselves. If you can't tell your story at the bar and have people enraptured - all by yourself -, or, for the introverts, tell it on paper for children and quieter people to be lost in, your story sucks.

If you think a story is a "narrative", you are an idiot. Read Aristotle to learn the difference, and learn about who Jean-François Lyotard was.

If you are using a template or formula to work out the contents of your story, you suck as a storyteller.

Stories end with a "moral" for a reason: they are how humans pass on moral education about the intrinsic harmatia of our condition, or our State of Nature. They are not formulaic, linear sequences of events aiming to be thrilling. Nor are they social science "activist" projects to "program" messages into the audience. If you remove the moral element of the endeavour, you have nothing.

What is the moral of Pygmalion or Cinderella? Is it the feminist sociology nonsense about stereotypical presentation of women as subservient to men? No, the opposite. Its moral is love transcends human pretense like class or strata. Is The Godfather a glorification of violence and patriarchal hierarchy? No, the opposite. Its moral is corruption of the best is the worst.

Traditions are answers to problems we have forgotten we have.

Stories are not sociology. Nor are they studies or political vehicles.

Storytelling is about many things. But most importantly, its function originates in something deeper than reason, as Aristotle originally argued.