Recycling Archetypes, Fairytales, and Master Plots: where all your Hollywood movies come from

It’s a cruel irony, Aaron Sorkin cannibalised his view on artistic “recycling” from T.S Eliot’s brutal reflection of creative realpolitick:

“Good writers borrow from other writers. Great writers steal from them outright.”

The great scientist, Issac Newton, simply acknowledged his inspirations: “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants”. One of the key identifying markers of contemporary — some might argue postmodern — writers in the field of Western cinema that has emerged from the open Hollywood battlefield, is a distinctive lack of understanding of basic literary theory.

Uneducated writers write diluted mess

It’s clear from just one evening’s viewing of US network drama, just like lunchtime soap operas, or Telenovelas, that the writers have almost no foundation in classical literature or its academic application, or even Grecian thought, such as the staple of all drama, “Poetics”. This is becoming pervasive in Hollywood’s product.

The results are becoming more and more horrific as the bankruptcy sets in: melodramatic spectacle replaces substance to attract the crowd to the circus; nationalistic exceptionalism replaces situational nuance; and gratuitous exhibitionism replaces moral/ethical exploration.

Why does it matter?

On a cultural level, because art is not something you devalue by putting in a consumable plastic box that you can take back to customer service when you‘re dissatisfied it doesn’t confirm your existing tastes and prejudices.

On an individual level, because if you don’t understand dramatic and literary theory, your stories suck. And when lots of writers’ stories start to suck on a generational level, everyone loses out.

Or as Matthew Vaughn puts it, much less diplomatically:

“Hollywood’s like a bunch of pigs in a trough, not realizing that food is running out and just eating it as quickly as possible.”

The open secret of story-telling

Solomon observed it morbidly in Ecclesiastes:

“What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”

Almost all stories and characters are re-telling another, older story in a new way. All characters are found somewhere else before, with the same consequences, and/or rewards. The only difference is the modernity of the backdrop and its technological features. The elements of the stories themselves are the same. Human nature doesn’t change, and drama specialises in illuminating the human condition.

With this, almost any literary agent finds a way to encapsulate the paragon of a “marketable” work as something that is “uniquely familiar”. The impossible task of screenwriters everywhere: to create something entirely original, which is also something viewers recognise because it’s a comfy narrative we’ve seen before.

For example: take “Avatar”, which is the familiar re-telling of the infamous “going native” template of “Pocahontas” recycled on another planet. Or “Raiders of the Lost Ark”, which is almost a scene-for-scene re-make of “Secrets of the Incas”, which is a copy of, and so on. Every “meet-cute” scene in every romantic comedy ever gets the same treatment; “Pretty Woman” is more a re-versioning of Shaw’s “Pygmalion” than “Cinderella”.

Shakespeare arguably “recycled” almost all of his stories from Grecian tragedies, and in particular, his personal influences, such as Plutarch and Chaucer. Hamlet, for example, bears striking similarities to the Greek tragedy of “Electra”. Only “Love’s Labour’s Lost”, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, “The Merry Wives of Windsor”, and “The Tempest” are his originals.

Really? Yes.

http://www.shakespeare-w.com/english/shakespeare/source.html

So, what were/are these stories we re-tell, and who were/are these characters we always re-cast?

The basics of any story, ever

Excepting cavemen paintings and biblical tales, the formalised answer typically lies in the roots of Greek tragedy. The first academic structuring of the sophisticated arts (music, poetry, theatre, etc) was put into place by the great minds and original literary storytellers in years BC — then copied and developed, over and over, and over, by those writers who studied them.

Greek philosophers grouped arguments (and fallacies) into 3 “appeals” to an audience to entice them into agreeing with a particular point of view:

Ethos: the credibility of a subject or author.

Pathos: the emotion (e.g. pity) of a subject.

Logos: the logical reasoning of a subject.

It’s also worth re-capping terms Aristotle used in “Poetics” for his “beginning/middle/end” 3-Act structure which defines “complexity” as a “reversal of fortunes”:

Mimesis: forming a picture in the viewer’s mind (poetic imitation of reality).

Mythos: the plot, or message structure of the work.

Opsis: the physical and visual presentation of the drama.

Hamartia: the “tragic flaw” or “sin” which sets the tragedy in motion.

Desis: the “tying” together of story elements that result in the end.

Dianoia: spoken thought from the participants to explain events.

Lexis: the expression of the meaning of words.

Anagnorisis: a point of discovery, or incident that sparks the story events.

Peripeteia: a reversal of fortunes from either direction.

Lusis: the “untying” of the story’s “mess” into a climax.

Katharsis: the audience’s emotional “purging” from experiencing the story.

We can conclude that the mythos pulls together a character archetype with a specific Hamartia to go through his/her Anagnorisis and Peripeteia as the Desis dissolves into Lusis, to deliver Katharsis to the audience in denouement— all to reveal a Moral, which is argued through credibility, emotion, or reason. Every time it involves a reversal in fortunes.

The 16 master archetypes

An archetype is a basic model from which copies are made; a prototype. In literary theory, people are, — unsurprisingly — “characterised” by giving them arch or stereo-typical attributes viewers recognise.

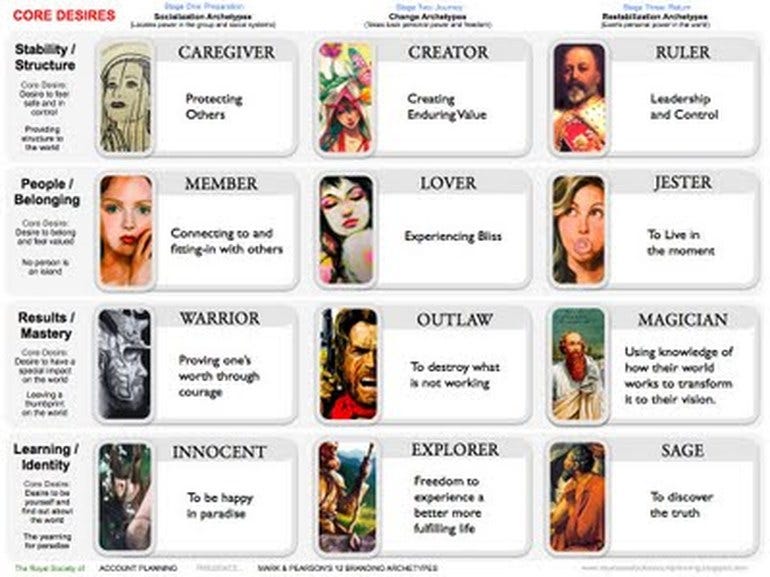

According to psychologist Carl Jung (from whose work the 16 Myers Briggs personality types are derived), archetypes emerge in literature from the “collective unconscious” of the human race. Northrop Frye, in his Anatomy of Criticism, explores archetypes as the symbolic patterns that recur within the world of literature itself. In both approaches, archetypical themes include birth, death, sibling rivalry, and the individual versus society.

The quintessential ancient dual archetypes are derived from the Grecian tragedy of Aristotle’s age, and personify “ethos”, or the guiding ideals of a personal “template”.

And here, we have a striking deviation and complexity that contemporary writing has mindlessly junked in favor of the more simplistic idea of a “protagonist” fighting against an “antagonist”. The Grecian archetypes, like comedy and tragedy themselves, and two sides of exactly the same coin.

There are no “good” or “bad” archetypes. They are dichotomous, immediately indicating moral complexity. People are not inherently one type or another. Their forms are expressing in the intensity of their same characteristics, on a very, very wide spectrum. An understanding of this very simple insight into characterisation could catalyse modern screenwriting, in and of itself: there are no goodies or baddies; their goodness or badness is in how those attributes are expressed, and on which end of the spectrum — also making them entirely fluid to move across it, at will, or the mercy of circumstance.

Or to put it more plainly, our hero could also be our villain under different circumstances, and vice versa.

Best summed up in Victoria Lynn Schmidt’s classic “45 Master Characters”, the main male and female templates can be broadly categorised from mythology.

First up, the men. Notice the influence of force, and little variance inage.

Apollo: Businessman (good side) vs. Traitor (bad side)

Ares: Protector (good side) vs. Gladiator (bad side)

Hades: Recluse (good side) vs. Magician (bad side)

Hermes: Jester (good side) vs. Derelict (bad side)

Dionysus: Ladies’ Man (good side) vs. Womaniser (bad side)

Osiris: Saviour (good side) vs. Punisher (bad side)

Poseidon: Artist (good side) vs. Abuser (bad side)

Zeus: King (good side) vs. Dictator (bad side)

Anakin Skywalker is a classic Osiris: the Chosen One born to bring balance to the Force as the galaxy’s Savior, who falls to the dark side and slides over the spectrum to become it’s Punisher. His son Luke, is arguably his Hades in a “parallax” narrative transitioning similarly: a timid Recluse who becomes a Jedi Magician. (Note: Schmidt argues Luke is Osiris again).

Then, the women. Notice the emphasis on cunning/betrayal, increasednuance, and the wider spectrum of age.

Aphrodite: Beautiful Muse (good side) vs. Femme Fatale (bad side)

Artemis: Feminist (good side) vs. Medusa (bad side)

Athena: Father’s Daughter (good side) vs. Backstabber (bad side)

Demeter: Nurturer (good side) vs. Controlling Mother (bad side)

Hera: Matriarch (good side) vs. Scorned Woman (bad side)

Hertia: Mystic (good side) vs. Betrayer (bad side)

Isis: Saviour (good side) vs. Destroyer (bad side)

Perisphere: Innocent maiden (good side) vs. Troubled teen (bad side)

The classic Artemis is Ripley in “Alien”, a powerful feminist who literally battles with her Gorgon in the form of the Alien Queen, later even becoming a clone “mother” to the creature.

Immediately we notice — absolutely immediately — that any of these characters are more interesting than anything in cinema of the last few decades. We swing from one end of the spectrum to the other in extremis, and we can also see how our character can change, transform, or distort between good and bad. And most crucial of all, we can see that the most powerful and memorable stories we recall from childhood or the cinema always involve an implementation of these very powerful archetypes.

There’s something incredibly compelling in understanding our villain could be the hero. Or that the hero is the same as the villain. Moriarty is just Holmes in another guise: all it takes is the Fall of Eden to separate the mirror image.

But we also can surmise that the transition from good to evil is far more dramatic, than the inverse. The catalyst back to good is always love; the Fall to evil comes from slavery to human nature. Here, mythology begins to reflect religious doctrine: the internal human conflict between agape (unconditional divine love) and the evil corruption of the flesh. Hamartia itself is even the greek biblical word for “sin” (falling short of the mark).

There are only X many story plots

Finally, once we chosen one or more of our character archetype derivations with their Hamartia, we come on to the nature of plot. What a story plot actually is.

The key is in the blindingly obvious: a conspiracy is underfoot; something is being plotted. A conspiracy of stupidity or error (comedy), or one of evil (tragedy). A conspiracy is a plot, and a plot is a conspiracy. Without a conspiracy being driven by a force, there is no story, just a banal timeline of events. Even “Road Trip” involves a conspiracy of sorts — to travel across the country.

Note: the protagonist does not drive the plot. The plot is an invisible force that drives the story.

Aesop wrote about only 2 “invisible forces”: conspiracies of strength(the Lion) and cunning (the Fox). Dante, echoing Cicero, then distinguished crimes into those of violence (forta) and fraud (forde). These of course in themselves mirror comedy and tragedy — comedy being farcical and fraudulent, and tragedy exploring the consequences of the use of force.

The exclusive number of story plot “templates” has been debated — and hence, varied — for decades. In order of increasing number:

Three: Colin Jackson

“There are only three stories proven to engage an audience. I choose to name them ‘Hubris’, ‘Discardation’ and ‘New Order’.” Hubris is the sin of pride, which will be punished (Jurassic Park); Discardation is the loss of something (E.T.), and New Order is an attempt to achieve change (Star Wars).”

The Unspecified Abstract 7 Plots

- [wo]man vs. Nature

- [wo]man vs. [wo]man

- [wo]man vs. the Environment

- [wo]man vs. Machines/Technology

- [wo]man vs. the Supernatural

- [wo]man vs. Self

- [wo]man vs. God/Religion

The 7 Basic Plots — Christopher Booker

Overcoming the Monster: The protagonist sets out to defeat an antagonistic force (often evil) which threatens the protagonist and/or protagonist’s homeland.

Rags to Riches: The poor protagonist acquires things such as power, wealth, and a mate, before losing it all and gaining it back upon growing as a person.

The Quest: The protagonist and some companions set out to acquire an important object or to get to a location, facing many obstacles and temptations along the way.

Voyage and Return: The protagonist goes to a strange land and, after overcoming the threats it poses to him or her, returns with nothing but experience.

Comedy: Light and humorous character with a happy or cheerful ending; a dramatic work in which the central motif is the triumph over adverse circumstance, resulting in a successful or happy conclusion.

Tragedy: The protagonist is a villain who falls from grace and whose death is a happy ending.

Rebirth: During the course of the story, an important event forces the main character to change their ways, often making them a better person.

9 Themes — John Carroll

The Virtuous Whore

The Troubled Hero

Salvation by a God

Soulmate Love

The Mother

The Value of Work

Fate

The Origin of Evil

Self-Sacrifice

The 20 Master Plots — Ronald Tobias

Quest: The hero searches for something, someone, or somewhere. In reality, they may be searching for themselves, with the outer journey mirrored internally. They may be joined by a companion, who takes care of minor detail and whose limitations contrast with the hero’s greater qualities.

Adventure: The protagonist goes on an adventure, much like a quest, but with less of a focus on the end goal or the personal development of hero hero. In the adventure, there is more action for action’s sake.

Pursuit: the focus is on chase, with one person chasing another (and perhaps with multiple and alternating chase). The pursued person may be often cornered and somehow escape, so that the pursuit can continue. Depending on the story, the pursued person may be caught or may escape.

Rescue: somebody is captured, who must be released by the hero or heroic party. A triangle may form between the protagonist, the antagonist and the victim. There may be a grand duel between the protagonist and antagonist, after which the victim is freed.

Escape: a person must escape, perhaps with little help from others. In this, there may well be elements of capture and unjust imprisonment. There may also be a pursuit after the escape.

Revenge: a wronged person seeks retribution against the person or organization which has betrayed or otherwise harmed them or loved ones, physically or emotionally. This plot depends on moral outrage for gaining sympathy from the audience.

The Riddle: entertains the audience and challenges them to find the solution before the hero, who steadily and carefully uncovers clues and hence the final solution. The story may also be spiced up with terrible consequences if the riddle is not solved in time.

Rivalry: two people or groups are set as competitors that may be good hearted or as bitter enemies. Rivals often face a zero-sum game, in which there can only be one winner, for example where they compete for a scarce resource or the heart of a single other person.

Underdog: similar to rivalry, but where one person (usually the hero) has less advantage and might normally be expected to lose. The underdog usually wins through greater tenacity and determination (and perhaps with the help of friendly others).

Temptation: a person is tempted by something that, if taken, would somehow diminish them, often morally. Their battle is thus internal, fighting against their inner voices which tell them to succumb.

Metamorphosis: the protagonist is physically transformed, perhaps into beast or perhaps into some spiritual or alien form. The story may then continue with the changed person struggling to be released or to use their new form for some particular purpose. Eventually, the hero is released, perhaps through some great act of love.

Transformation: change of a person in some way, often driven by unexpected circumstance or events. After setbacks, the person learns and usually becomes something better.

Maturation: a special form of transformation, in which a person grows up. The veils of younger times are lost as they learn and grow. Thus the rudderless youth finds meaning or perhaps an older person re-finds their purpose.

Love: a perennial tale of lovers finding one another, perhaps through a background of danger and woe. Along the way, they become separated in some way, but eventually come together in a final joyous reunion.

Forbidden Love: when lovers are breaking some social rules, such as in an adulterous relationship or worse. The story may thus turn around their inner conflicts and the effects of others discovering their tryst.

Sacrifice: someone gives much more than most people would give. The person may not start with the intent of personal sacrifice and may thus be an unintentional hero, thus emphasizing the heroic nature of the choice and act.

Discovery: the hero discovers something great or terrible and hence must make a difficult choice. The importance of the discovery might not be known at first and the process of revelation be important to the story.

Wretched Excess: the protagonist goes beyond normally accepted behaviour as the world looks on, horrified, perhaps in realization that ‘there before the grace of God go I’ and that the veneer of civilization is indeed thin.

Ascension: the protagonist starts in the virtual gutter, as a sinner of some kind. The plot then shows their ascension to becoming a better person, often in response to stress that would defeat a normal person. Thus they achieve deserved heroic status.

Descension: a person of initially high standing descends to the gutter and moral turpitude, perhaps sympathetically as they are unable to handle stress and perhaps just giving in to baser vices.

The 36 Dramatic Situations — Carlo Gozzi/Georges Polti

Take a deep breath — apparently there are 10,000 combinations.

- Supplication (in which the Supplicant must beg something from Power in authority)

- Deliverance

- Crime Pursued by Vengeance

- Vengeance taken for kindred upon kindred

- Pursuit

- Disaster

- Falling Prey to Cruelty of Misfortune

- Revolt

- Daring Enterprise

- Abduction

- The Enigma (temptation or a riddle)

- Obtaining

- Enmity of Kinsmen

- Rivalry of Kinsmen

- Murderous Adultery

- Madness

- Fatal Imprudence

- Involuntary Crimes of Love (example: discovery that one has married one’s mother, sister, etc.)

- Slaying of a Kinsman Unrecognized

- Self-Sacrificing for an Ideal

- Self-Sacrifice for Kindred

- All Sacrificed for Passion

- Necessity of Sacrificing Loved Ones

- Rivalry of Superior and Inferior

- Adultery

- Crimes of Love

- Discovery of the Dishonor of a Loved One

- Obstacles to Love

- An Enemy Loved

- Ambition

- Conflict with a God

- Mistaken Jealousy

- Erroneous Judgement

- Remorse

- Recovery of a Lost One

- Loss of Loved Ones.

Of course, we arguably need to update it with the missing 37th: “Mistaken Identity”.

69 (Unknown) Plots — Rudyard Kipling

Only one problem. According to Tobias, Mr Kipling didn’t say what they were.

But of course, one “theory” trumps them all in screenwriting reference books. The titan of stupid, and such a gross distortion of Greek tragedy that it deserves its own library classification:

According to an article on SMH:

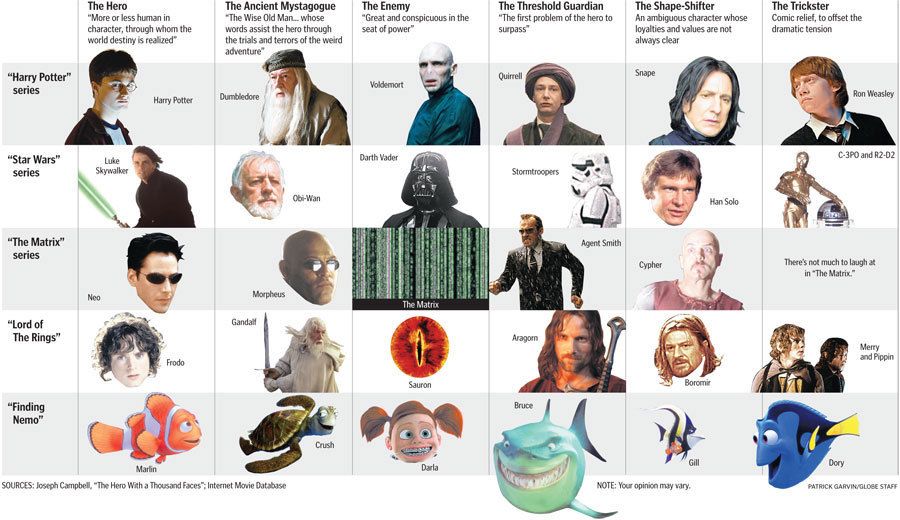

“Hollywood got obsessed with “The Hero’s Journey” in the mid-1980s after a Disney script editor named Christopher Vogler wrote a memo suggesting elements of that classic tale could be discerned in every successful movie, including comedies. Producers thought Vogler had hit upon what they’d been seeking all their careers: The Magic Formula, or The Quick Fix. They started demanding that screenwriters insert mentors, threshold guardians, and innermost caves into every script.”

That sums it up all too well. Copies of “The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers“ and “A Practical Guide to The Hero with a Thousand Faces” need to be piled up and publicly burned for being the ignorant toilet paper travesty they are, alongside Stephanie Meyers’ anthology.

That is why almost every “plot” to every major movie in the last 30 years has had to have a “hero” doing “the right thing”, rather than… drama.

Zombies are still the fairytale of Frankenstein

When you can’t get to “unique”, “familiar” is always much easier. The supposedly “original” plotlines of the endlessly re-told “zombie” genre always re-create the same classic of Frankenstein’s Monster: the dead becoming re-animated by a bizarre confluence of affairs, or botched scientific experimentation.

Some themes are perpetual:

- The dead coming back to life (vampires, zombies)

- Romance across social classes;

- Love for a monster

- The defeat of a monster (werewolves, greek myths etc);

- Travelling in time, and

- so on, and on, ad nauseam.

The most famous fairytales — many with fairly horrific origins — are found in one well-known source: German academics Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, who specialized in collecting and publishing folklore during the 19th century, and published “Children’s and Household Tales” (“Kinder- und Hausmärchen”) in 1812.

Inside were “Cinderella” (“Aschenputtel”), “The Frog Prince” (“Der Froschkönig”), “The Goose-Girl” (“Die Gänsemagd”), “Hansel and Gretel” (“Hänsel und Gretel”), “Rapunzel”, “Rumpelstiltskin”(“Rumpelstilzchen”),”Sleeping Beauty” (“Dornröschen”), and “Snow White” (“Schneewittchen”).

At first glance, these classic childrens’ stories don’t bear too much resemblance to the films we know today, unless of course, we look at Pixar’s portfolio. However, strip them down to the basics, and it starts to become a little clearer.

The logline for “Cinderella”, the classic “Ugly Duckling” and “Rags to Riches” tale from Pygmalion:

“A servant girl is taken by her godmother to a ball and, after proving her identity the next day, wins the heart of a handsome prince.”

Sadly, that’s not quite enough for screenwriters who think they need cliched “conflict” and “obstacles” in absolutely everything, everywhere. It gets butchered up as:

“With the help of her godmother, a downtrodden servant girl overcomes the obstacles raised by her ugly step-sisters, attends her dream ball, and finds the confidence next day to step forward and win true love.”

Components:

- A downtrodden girl of lower class

- A powerful suitor of higher class

- A high-profile event to go to

- Jealous and bitchy saboteurs

Yep, that’s “Pretty Woman”, “Ever After”, “What a Girl Wants”, “Rags”, “Fifty Shades of Grey”, and almost any US high-school movie where the girl involved is socially-isolated and involved with a richer old jock before a prom (“She’s All That”). Just as every romantic comedy involving a rough-type man overcoming a “difficult” woman who dislikes him is a copy of “Taming of the Shrew”, and every trio of men on an adventure ends up as “The Three Musketeers”, every detective is Holmes, every villainous scientist is Jekyll, and every animal-human comedy is “Dr Doolittle”. Jane Austen in the reference for period drama; H.G Wells the father of all Sci-Fi.

The recycling of the oldest templates goes on and on: “Clueless” (Emma), “Cruel Intentions” (Les Liaisons Dangereuses), “Ghosts of Girlfriends Past” (A Christmas Carol), “Bedazzled” (Faust), “Trading Places” (Prince and the Pauper), “The Lion King” (Hamlet), “Easy A” (Scarlett Letter), “A Knight’s Tale” (Canterbury Tales), “The Nutty Professor” (Jekyll & Hyde), “Spike” (Beauty and the Beast), “Twilight” (Romeo & Juliet), “She’s the Man” (Twelfth Night), “Independence Day” (War of the Worlds), and on, and on, and on.

For all the templates you can see in all films:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_fairy_tales

Ending once upon a time

And why do we seal the end with the kiss? Over to the Bard once again, the Great Plagiarist, with Feste’s prophetic song in “Twelfth Night”:

“Journeys end in lovers meeting”

Journeys are resolved when the fracture heals, and the breath (or spirit) of two souls commune into one, signifying the conclusion of our tale, and its Katharsis. Or as the Hollywood cynic will tell you, it’s time for some uplighting music over the credits, so you’ll leave with the contagious mood of the music — feeling like you had an amazing time.