Has The Sexual Revolution Been A Regression To Bonobo Primate Behaviour?

"I lived for years in a sexually liberated lesbian commune", writes the brilliant Mary Harrington. After six decades of observed evidence, it's impossible to escape the allegation the Swinging Sixties weren't progress at all, and the "liberation" they championed was a degeneration back to our primate beginnings. One of our ancestral species in the evolutionary line appears to share more with today's militants than any other, and its clash with the physically-larger male-dominated species.

As Mary puts it:

"Around the same time, I also discovered that the supposedly egalitarian and sexually liberated all-lesbian community I lived in was in fact hierarchical and riddled with competition. Whether the issue was who was cleaning the kitchen or who was sleeping with whom, excluding males from the household did not vanquish rivalry and exploitation."

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-11791181/I-lived-years-sexually-liberated-lesbian-commune-true-peace-married-man.html

This Ultra-Radical Female Behaviour Looks Awfully Familiar

Academics are often desperate to promote ideology into science to ferment Lysenkoism. One of the ways they do this is to mine and revise evidence of matriarchal societies to support their future Marxist ambitions. There's a reason matriarchies died out.

Female researchers at Arizona State think female-dominated monkey societies are a "model for evolution of human peacemaking" (https://news.asu.edu/20220621-bonobo-behavior-hints-model-evolution-human-peacemaking), and female staff at Inside Science claim they "lead the way" (https://www.insidescience.org/news/bonobo-matriarchs-lead-way).

In 2006, there was a strange article in Scientific American discussing studies carried out at the San Diego zoo. The following extract has been heavily edited as a thought experiment; read it with an open mind using your own knowledge of the last thirty years.

The species is best characterized as female-centered and egalitarian and as one that substitutes sex for aggression. Whereas in most other species sexual behavior is a fairly distinct category, it is part and parcel of social relations--and not just between males and females. They engage in sex in virtually every partner combination (although such contact among close family members may be suppressed).

They become sexually aroused remarkably easily, and they express this excitement in a variety of mounting positions and genital contacts. Furthermore, the frontal orientation of the female vulva and clitoris strongly suggest that the female genitalia are adapted for this position.

Instead of a few days out of her cycle, the female is almost continuously sexually attractive and active.

Perhaps the most typical sexual pattern is genito-genital rubbing (or GG rubbing) between adult females. One female facing another clings with arms and legs to a partner that, standing on both hands and feet, lifts her off the ground. The two females then rub their genital swellings laterally together, emitting grins and squeals that probably reflect orgasmic experiences.

Males, too, may engage in pseudocopulation but generally perform a variation. Standing back to back, one male briefly rubs his scrotum against the buttocks of another. They also practice so-called penis-fencing, in which two males hang face to face from a branch while rubbing their erect penises together.

The diversity of erotic contacts includes sporadic oral sex, massage of another individuals genitals and intense tongue-kissing. Their sexual activity is rather casual and relaxed. It appears to be a completely natural part of their group life.

Rather than being male-bonded, their society gives the impression of being female-bonded, with even adult males relying on their mothers instead of on other males.

The bonding among females violates a fairly general rule, outlined by Harvard University anthropologist Richard W. Wrangham, that the sex that stays in the natal group develops the strongest mutual bonds. They are unique in that the migratory sex, females, strongly bond with same-sex strangers later in life. In setting up an artificial sisterhood, they can be said to be secondarily bonded. (Kinship bonds are said to be primary.)

Their society is, however, not only female-centered but also appears to be female-dominated.

It all sounds a bit like Weimar Berlin or West Hollywood.

Does any of this sound familiar? Matriarchy and same-sex group sexual behaviour as a form of bonding and conflict resolution, often around feeding?

As the article begins:

The bonobo shares more than 98 percent of our genetic profile, making it as close to a human as, say, a fox is to a dog. The split between the human line of ancestry and the line of the chimpanzee and the bonobo is believed to have occurred a mere eight million years ago. The subsequent divergence of the chimpanzee and the bonobo lines came much later, perhaps prompted by the chimpanzees need to adapt to relatively open, dry habitats.

Pygmy chimpanzees, one of our nearest genetic relatives, exist in a female-dominated sexually-obsessed society.

"Bonobo Sex and Society: The behavior of a close relative challenges assumptions about male supremacy in human evolution"

(Frans B. M. De Waal, Dutch primatologist and ethologist, Charles Howard Candler Professor of Primate Behavior in the Department of Psychology at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia)

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/bonobo-sex-and-society-2006-06/

Science 101: What Are Bonobos?

They're cute miniature chimps. And unbelievably lovable. They live in the Congo. The biggest population outside there is in San Diego.

Pgymy chimps, or Pan paniscus, do indeed exhibit a unique and complex sexual behaviour that plays a significant role in their social structure. Their sexual activity is not limited to reproduction but also serves various other purposes, including social bonding, conflict resolution, and stress relief.

Bonobos are known for their promiscuous and relatively relaxed sexual behaviors. They engage in sex for various reasons, such as forming social bonds, reducing tensions, and maintaining group harmony. Their sexual behaviors are a natural part of their social structure and have been adapted over time to suit their specific ecological and social needs.

Some key aspects of bonobo sexual behaviour include:

- Frequent and diverse interactions: Bonobos engage in sexual activity more frequently than other primates and display a wide variety of sexual positions and partner pairings. They participate in heterosexual, homosexual, and even bisexual encounters.

- Non-reproductive mating: Unlike many other species, bonobos do not restrict sexual activity to fertile periods. They mate throughout the year, regardless of the females' estrous cycles, and engage in sexual behaviour for reasons beyond reproduction.

- Social bonding: Sexual interactions help establish and maintain strong social bonds among bonobos. This bonding contributes to their relatively peaceful and cooperative society.

- Conflict resolution: Bonobos use sexual activity as a means to reduce tension and resolve conflicts within the group. It helps prevent aggressive behaviour and maintain harmony.

- Stress relief: Bonobos engage in sexual activity to alleviate stress, which can arise from various sources, such as competition for resources, social disputes, or environmental pressures.

However, they are very different to chimps, sexually-speaking. Some of the key differences include:

- Frequency and variety: Bonobos engage in sexual activity more frequently than chimpanzees, and they display a wider variety of sexual positions and partner pairings, including heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual encounters. In contrast, chimpanzees primarily engage in heterosexual mating, with occasional instances of homosexual behaviour.

- Non-reproductive mating: Bonobos engage in sexual activity for various reasons beyond reproduction, such as social bonding, conflict resolution, and stress relief. They mate throughout the year, regardless of the females' estrous cycles. Chimpanzees, on the other hand, typically engage in sexual activity during the females' estrous cycles, primarily for reproductive purposes.

- Female sexual behaviour: Female bonobos are more sexually active than female chimpanzees and often initiate sexual encounters. They may also engage in genital-genital rubbing (called GG-rubbing) with other females to form and maintain social bonds. Female chimpanzees are less likely to initiate sexual activity and do not exhibit the same level of same-sex interactions.

- Sexual behaviour in social context: Bonobos use sexual activity as a means of reducing tension, resolving conflicts, and fostering cooperation within their group, contributing to their relatively peaceful social structure. In contrast, chimpanzee societies are more hierarchical and competitive, with aggression and dominance playing more significant roles in their interactions.

- Male competition and mating strategies: Chimpanzee males often compete aggressively for access to sexually receptive females and may form temporary coalitions to enhance their mating success. Bonobo males are less aggressive in their mating strategies and rely more on social bonding and relationships with females to gain access to mates.

This characteristic set of behaviours has positive and negative effects on their evolutionary selectivity:

- Social cohesion: Frequent sexual activity in bonobos helps maintain strong social bonds and cohesion within the group. This promotes cooperation, which can enhance the group's ability to secure resources, defend against predators or rival groups, and care for offspring.

- Reduced aggression: Bonobos use sexual activity to diffuse tension, resolve conflicts, and establish social hierarchies. This reduces the likelihood of serious injuries or fatalities due to violent confrontations, which can be detrimental to the group's overall fitness.

- Genetic diversity: The promiscuous mating behaviour of bonobos results in a higher degree of genetic diversity within the population. This can be advantageous for the species, as it increases the likelihood of producing offspring with a diverse range of traits, some of which may be beneficial for survival and adaptation to changing environments.

But it can also be extremely negative:

- Increased disease transmission: Frequent and promiscuous sexual activity can increase the risk of transmitting sexually transmitted infections (STIs) within the group. High prevalence of STIs can lead to reduced reproductive success, morbidity, and mortality, negatively affecting the evolutionary fitness of the population.

- Lower parental investment: In bonobo societies, where sexual activity is not limited to long-term pair-bonds, there is less certainty of paternity. This can result in lower parental investment from males compared to species with more monogamous mating systems. However, this effect might be mitigated by the cooperative nature of bonobo societies, where multiple individuals, including non-parents, contribute to the care of offspring.

- Reduced mate selection based on physical traits: The emphasis on social factors in bonobo sexual behaviour may lead to less selective pressure for the development of physical traits related to reproductive success. In some species, competition for mates leads to the evolution of traits that signal good genes or high fitness. In bonobos, the reduced competition due to their more egalitarian and promiscuous mating system may result in less pressure for such traits to evolve.

Important source material for background reading:

- de Waal, F. B. M. (1995). Bonobo Sex and Society. Scientific American, 272(3), 82-88. Link: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24981525

- Furuichi, T. (2011). Female contributions to the peaceful nature of bonobo society. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 20(4), 131-142. Link: https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.20308

- Hohmann, G., & Fruth, B. (2000). Use and function of genital contacts among female bonobos. Animal Behaviour, 60(1), 107-120. Link: https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2000.1451

- Parish, A. R. (1996). Female relationships in bonobos (Pan paniscus): evidence for bonding, cooperation, and female dominance in a male-philopatric species. Human Nature, 7(1), 61-96. Link: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02734133

- Vervaecke, H., & Stevens, J. M. (2010). Grooming and coalitions in Pan paniscus: male and female patterns. International Journal of Primatology, 31(2), 259-277. Link: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-010-9388-3

- Hohmann, G., & Fruth, B. (2003). Lui Kotal: A new site for field research on bonobos in the Salonga National Park. Pan Africa News, 10(2), 25-27. Link: http://mahale.main.jp/PAN/10_2/10(2)-pdfs/10(2)-25.pdf

- Clay, Z., & Zuberbühler, K. (2011). Bonobos extract meaning from call sequences. PLoS ONE, 6(4), e18786. Link: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0018786

- Surbeck, M., Hohmann, G., & Fruth, B. (2011). Reproductive strategies and the influence of mothers on the development of social bonds in wild bonobos (Pan paniscus). Behaviour, 148(9-10), 1147-1169. Link: https://doi.org/10.1163/000579511X596599

- White, F. J., & Wood, K. D. (2007). Female feeding priority in bonobos, Pan paniscus, and the question of female dominance. American Journal of Primatology, 69(8), 837-850. Link: https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20387

- Fruth, B., & Hohmann, G. (2006). Social grease for females? Same-sex genital contacts in wild bonobos. In V. Sommer & P. L. Vasey (Eds.), Homosexual Behaviour in Animals: An Evolutionary Perspective (pp. 294-315). Cambridge University Press. Link: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511542348.013

How Similar Are They To Humans?

While bonobos and humans are genetically closely related, there are both similarities and differences in sexual behaviours. Some of the similarities include:

- Diversity of sexual activities: Like humans, bonobos exhibit a wide range of sexual activities and positions. They engage in heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual encounters, which demonstrates a level of sexual diversity also observed in human populations.

- Non-reproductive mating: Both bonobos and humans engage in sexual activities for reasons beyond reproduction. Emotional bonding, pleasure, stress relief, and conflict resolution are some of the motivations for sexual behaviour shared by both species.

- Emotional and social bonding: In both bonobos and humans, sexual activities can help establish and maintain emotional connections and social bonds between individuals. This is particularly evident in the long-term relationships humans form and the strong social bonds observed among bonobos.

- Importance of social context: Social factors play a crucial role in shaping sexual behaviour in both bonobos and humans. For example, social status, relationships, and cultural norms can influence mating choices and patterns in human societies, while social bonds and alliances are key determinants of mating access in bonobo societies.

However, there are also notable differences between bonobo and human sexuality:

- Frequency of sexual activity: Bonobos engage in sexual activities more frequently than humans, and their sexual behaviour is more visibly integrated into their daily social interactions.

- Role of monogamy and pair-bonding: Humans form long-term monogamous relationships or pair-bonds, which may be related to parental investment and the extended period of child-rearing. Bonobos, in contrast, are more promiscuous and do not exhibit the same level of long-term pair-bonding.

- Cultural norms and taboos: Human sexuality is heavily influenced by cultural norms, values, and taboos, which can vary widely across societies. Bonobo sexuality, on the other hand, does not involve such complex cultural influences.

- Sexual dimorphism and competition: Humans exhibit greater sexual dimorphism than bonobos, with males being larger and more muscular than females. This can result in more aggressive male competition for mates in human societies. Bonobos, in contrast, have reduced sexual dimorphism and display less aggressive mating strategies.

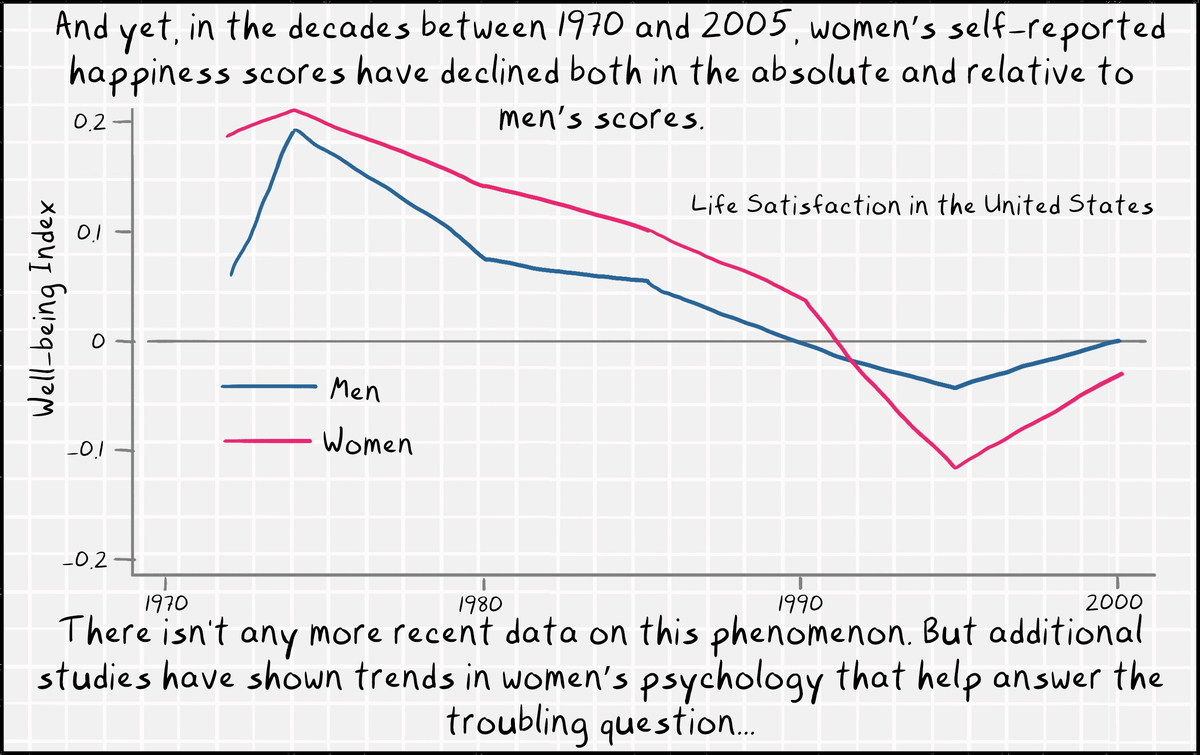

The Disaster Of The 60s Sexual Revolution

The "sexual revolution" that occurred after the introduction of the birth control pill in the 1960s brought about significant changes in human female sexual behaviour, as well as in societal attitudes and behaviours surrounding sex and relationships.

Some of the most serious effects this catastrophe had were:

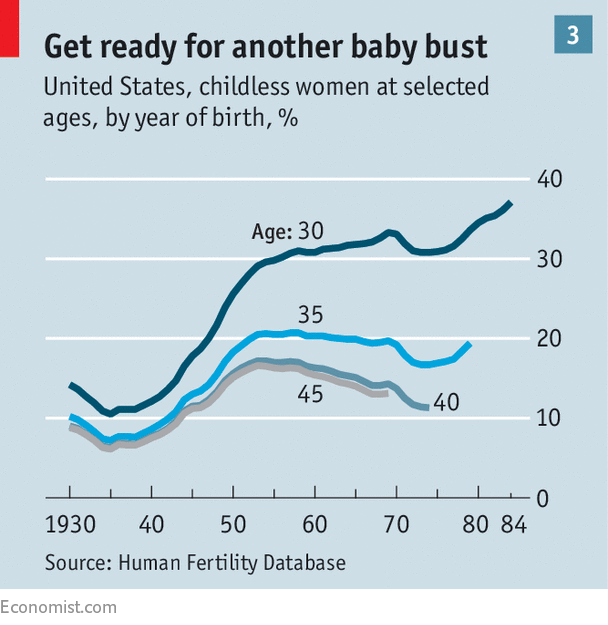

Declining birth rates

The widespread availability of contraceptives and the shift in societal attitudes towards sex and reproduction led to a decline in birth rates in many developed countries. This decline has contributed to aging populations and potential challenges in providing social services and healthcare for older generations.

"World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision" by United Nations: https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2017_KeyFindings.pdf

The global fertility rate declined from 5.0 children per woman in 1950-1955 to 2.5 children per woman in 2010-2015.

Increased sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

With more people engaging in casual sex and having multiple partners, the risk of sexually transmitted infections increased. Although the availability of contraceptives like condoms helped control the spread of STIs to some extent, the prevalence of infections like HIV/AIDS, gonorrhea, and chlamydia increased during the period following the sexual revolution.

"Trends in Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States: 2000 Annual Data for the Health of the Nation" by CDC : https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats00/slides.htm

Between 1950 and 2000, the reported cases of gonorrhea in the United States increased from around 90,000 to over 300,000 cases.

Collapsing family structures

The sexual revolution contributed to a shift in traditional family structures, with an increase in single-parent households, cohabitation, and non-marital births. While these changes reflect greater diversity in family structures, they have also been associated with potential negative consequences for child development and wellbeing in some cases.

"World Family Map 2017: Mapping Family Change and Child Well-being Outcomes" by Institute for Family Studies: https://ifstudies.org/ifs-admin/resources/world-family-map-2017.pdf

The percentage of children living with both parents in the United States declined from 85% in 1960 to 65% in 2017.

Relationship instability

The sexual revolution's emphasis on individual freedom and personal fulfillment led to changes in expectations surrounding relationships, with some people prioritizing short-term satisfaction over long-term commitment. This shift contributed to an increase in relationship instability and divorce rates, which can have emotional, financial, and social consequences for individuals and families.

"Marriage and Divorce: Changes and Their Driving Forces" by Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Spring 2007: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.21.2.27

The crude divorce rate in the United States increased from 2.2 per 1,000 people in 1960 to 5.3 per 1,000 people in 1981.

Some aspects of human sexual behaviour became more similar to bonobo sexual behaviour after the sexual revolution, while others remained distinct.

Increased similarities after the sexual revolution:

- Non-reproductive mating: The birth control pill allowed human females to engage in sexual activities with reduced risk of unintended pregnancy, leading to an increase in sexual activity for pleasure, emotional bonding, and social connections, rather than solely for reproduction. This aspect of human sexuality became more similar to bonobo sexuality, where sexual activity is not limited to reproduction.

- Sexual freedom and expression: The sexual revolution led to a more liberal attitude toward sexuality and a greater acceptance of diverse sexual behaviours in human societies. This shift allowed for more open expression of sexuality, which, to some extent, resembles the open and frequent sexual interactions observed in bonobos.

However, there are still significant differences between human and bonobo sexual behaviour, even after the sexual revolution:

- Cultural norms and taboos: Human sexual behaviour continues to be shaped by cultural norms, values, and taboos that can vary widely across societies. These influences are not present in bonobo sexuality, which remains more consistent across different social groups.

- Role of monogamy and pair-bonding: While the sexual revolution led to more diverse relationship structures, many human females still engage in long-term monogamous relationships or pair-bonds. Bonobos, in contrast, are more promiscuous and do not exhibit the same level of long-term pair-bonding.

- Frequency of sexual activity: Even after the sexual revolution, human sexual activity is generally less frequent and less openly integrated into daily social interactions compared to bonobos.

So it's objectively fair to say some aspects of human female sexual behaviour became more similar to bonobo sexual behaviour after the sexual revolution, particularly in terms of non-reproductive mating and increased sexual freedom.

What exactly is it to be "liberated" back to a pre-human state of primate behaviour? How exactly is that... "progress"?

Maybe... just maybe...it wasn't about "liberation" at all, but something else. Maybe a political goal.