Everything We Know About Screenwriting Is Wrong

In academic circles, two of the most quoted scholars when discussing film are Harold Vogel, and Ian MacDonald. The former wrote “Entertainment Industry Economics: A Guide for Financial Analysis”, which establishes many of the accepted statistics of the field, such as there been an estimated 500,000 films in existence. The latter has produced a litany of informative papers on the craft of screenwriting, including “Screenwriting Poetics and the Screen Idea”, “The Presentation of the Screen Idea in Narrative FilmMaking”, and “Disentangling the Screen Idea”.

Whilst Vogel states that only 30% of films actually make money, MacDonald’s work contains the most terrifying statistic for any screenwriter; enough to chill the bones of the strongest scribe:

Only 2% of screenplays received are produced into movies.

Shudder. 98% of screenplays go absolutely nowhere.

That, and creativity theorists Csikszentmahalyi & Piirto’s “10 year rule”:

“Any person,” she [Piirto] claims, “must have been working in a domain for a minimum of 10 years in order to achieve international recognition”.

(Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York, NY: HarperCollins. Piirto, J. (2004). Understanding creativity. Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press, Inc.

But perhaps a more fascinating — and much broader — look at the problems involved in and around the process of screenwriting, are encapsulated by Newcastle University (AU) scholar Joe T Velikovsky, in his fascinating 2016 paper “Twenty-Four Problems in the Movie Screenwriting Domain”.

Velikovsky summarises 24 specific problems that are so self-evident, that it’s any wonder if anyone should trust what is written by and for screenwriters at all. Almost everything we assume is at best arguable, and at worst, entirely incorrect.

- Less than 2% of screenplays are produced.

Simple, easy to understand. And painful. - The dominance of US screenwork discourse in non-US cultures.

Screenwriting manuals are written by US authors, and few of them have any empirical process for selecting example material. - The dominance of quasi-Aristotelian ideas of drama.

Aristotle invented his guidelines in Poetics, his selections were arbitrary, and the US cinematic form is wrongly conflated with Greek Tragedy. - The misconception of “Aristotelian” “three-act” structure.

It doesn’t exist in Poetics, and it doesn’t have any apparent influence on a film’s success or failure. - Scene Length Prescriptions.

McKee’s 2.5min max prescription in “Story” isn’t based on anything other than his personal preference. - Transformational character `arcs’.

None of the protagonists in the top 20 films with the highest returns experience a “transformation” at all. - Mythic Structure (Hero’s Journey)

Monomyth stories are male-specific, and it has no empirical influence on success or failure. - Lack of a universal screen grammar/language.

Film grammar like “beat”, “shot” and “scene” has no quantifiable structure or reliable semiology. - The status and interrelationship of the UK film and TV drama industry with the global film economy, particularly in relation to Hollywood.

Self-explanatory. The British are over-represented in Hollywood. - The US dominates global media production.

For example, the UK’s industry is primarily funded from the US. - Screenwork readers (such as producers, script assessors, directors, actors) say they want “unique and original”, yet they also cannot define what that means.

Self-evident. The “uniquely familiar” story is an median average in a world of subjective opinion. - The definition of a “good” screenwork is still contested.

Again, self-evident. What’s good for the goose… - Writers feel that screenworks are frequently `dumbed down’ by financiers in a quest for overall audience reach.

There’s a producer pissing in a bowl of water. The writer, incredulous, asks him what he’s doing. His answer? “Making it better”. - Since Aristotle and the screenplay gurus (Field, Seger, McKee et al) currently dominate the discourse of screenwriting convention, the screen industry in general does not employ a consilient or empirical method in the study of successful screen stories.

These “teachers” and their books, are full of shit, and don’t have an empirical process for their examples. - Many in the field still operate under the (incorrect) assumption that other factors — beside the story alone — contribute significantly to the success or failure of a screenwork.

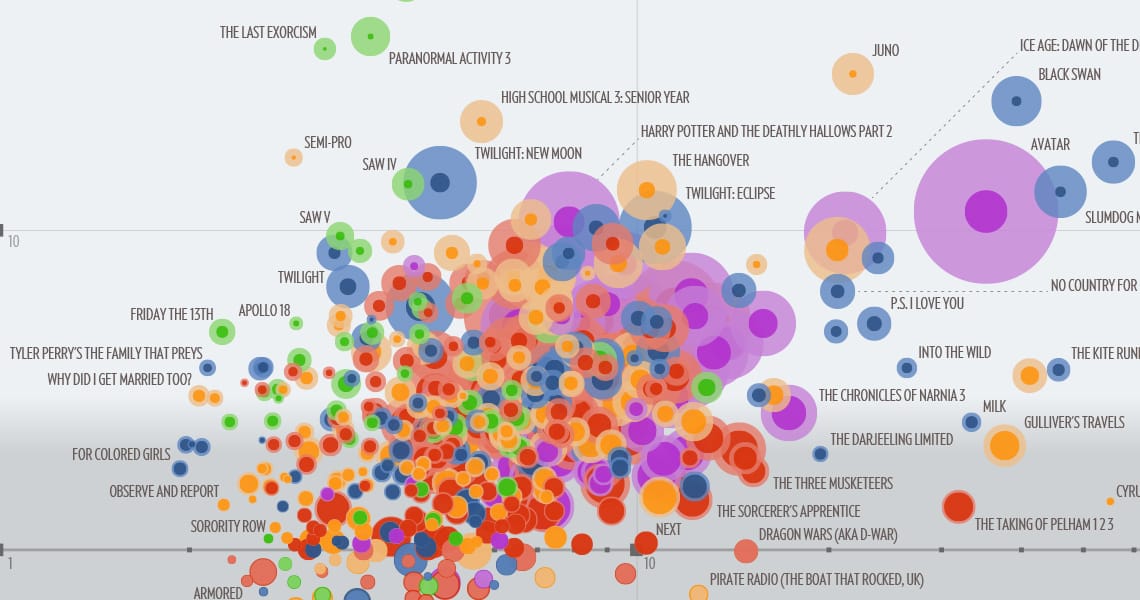

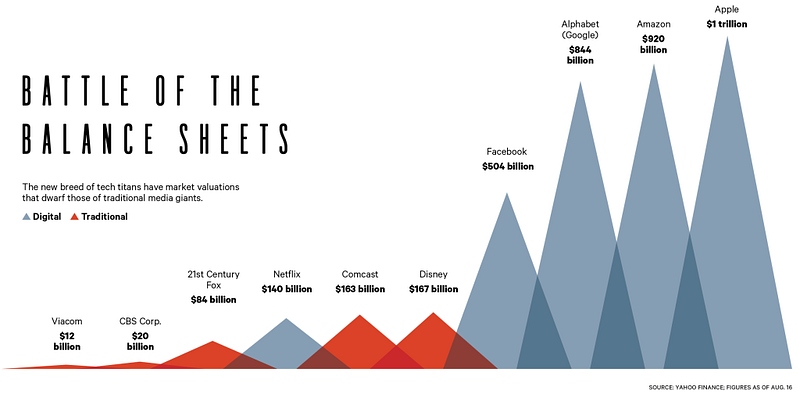

The authors of “Hollywood Economics” (lol!) show that marketing spend, star power or reviews do not affect the success/failure of a movie: character, creativity, and good storytelling “trump” everything else. - Producers and financiers sometimes overrule screenwriters for illogical reasons, or simply: because they can.

There is a reason writers are alcoholics. - In the dominant discourse of the screenwriting convention, little attention is paid to “writing to a budget.”

Screenwriters are pouring out their imagination, and disconnected from what the budget will be for their idea in the future. - Screenwriters are at the bottom of the screenwork hierarchy in film, despite that the story is the reason a film succeeds or fails to find an audience.

Writers have 2 choices: refuse to sell the script, or have their name removed. That’s it. - A Romantic rather than a rational view of creativity by screenplay gurus and therefore by readers in screen storytelling means that screenwriters are speaking a different language to financiers, producers, and screenwork readers.

The “Gurus” are completely full of shit, so young screenwriters are full of shit, and none of it is realistic to the people reading. - Terminological inconsistency in the field.

“Step Outline” and “Scene Breakdown” are the same thing, but have different names in the US and UK. - The current dominant view of screenwriting theory and practice in the screenwriting convention is a linear, micro, structuralist view, which for the most part ignores “the bigger picture”- that the screen industry is a set of overlapping bio-psycho-socio-geo-politico-cultural systems (see Hennessy & Amabile 2010), and also largely ignores Bourdieuian concepts of social trajectories, habitus, field, and agency and structure.

Self-evident, if you understand that type of thing. - Screenwork is conceived with a separation in conception (“writing”) and execution (“filmmaking”).

All 2o of the top returning films wrote AND produced them. - Conventional screenplay format may not be the best solution to the problem of representing the screen idea.

There are sometimes better ways: ad-lib, image-based, improvisation from outline. “The Format” isn’t necessarily the best. - The `Less Than 1% Problem’: Seven in ten films in the US lose money (Vogel 2011), and of the less than 2% of screenplays presented to producers, that are made.

Velikovsky’s own contribution: if 70% of films lose money, and 98% of screenplays go unproduced, then we’re looking at a success rate of 0.6.

So, what can we gleam from the empirical data and theorizing in the citations given with these criticisms? What common assumptions are actually nonsense and/or urban myth?

- The 3-Act structure doesn’t come from Poetics, and it has no effect on a film’s success or failure.

- American cinema has little in common with Greek Tragedy at all.

- Character “arcs” have little no effect on a film’s success or failure.

- The “Hero’s Journey” has little or no effect on a film’s success or failure.

- Producers can’t define what they want, there’s no empirical measurement for the quality of a work, and there’s no structure to the syntax.

- Writers’ approach to filmmaking is entirely disconnected from the reality of production.

- 0.6% of produced screenplays break even as a movie.

- Screenwriting “gurus” are utterly and almost universally full of shit.

One point stands out, which is in contract to Goldwyn’s pronunciation that “no-one knows anything”: Arthur DeVany’s argument in Hollywood Economics (p 4–6).

“The frightening thing about trying to manage this business is that there is no tangible means to reliably change the odds that a movie will succeed or fail. Marketing can’t change the odds. There is no evidence to show that marketing has much to do with a film’s success. Marketing is mostly defensive anyway; a studio has to market its films just to draw attention in a field where everyone is shouting. If you don’t shout too, you will be drowned out and may not be noticed.

When you take all the marketing together, it is probably a wash. A studio can gain a slight edge through marketing, but there is no gain at the industry level. But a temporary advantage, gotten through advertising, quickly washes away if the film doesn’t have the goods.

Nor can casting stars in movies increase the odds of success. Star movies cost a lot of money and have a tendency to run over budget. A single person just can’t put that much production value on the screen in a story involving many characters and events. It is a really strong performance in an outstanding film that makes a star. Movies make stars, not the other way around.

What then, do stars do for a movie? Aside from earning a higher least revenue, a star movie has only a slightly higher chance of making a profit than a non-star movie. If the star’s agent extracts the higher expected profit in the star’s fee, then the movie will almost certainly lose money. I call this the Curse of the Superstar.

Opening big and leading at the box office is a momentary success. A movie has to attain or sustain box-office dominance over many weeks to make major money. The size of the opening does not predict how the ensuing battles will evolve or how much money the film will take in.

None of our results is more surprising than finding that, hard-headed science puts the creative process at the very center of the motion picture universe. There is no formula. Outcomes cannot be predicted. There is no reason for management to get in the way of the creative process. Character, creativity, and good story-telling trump everything else.”

DeVany’s myth-busting is quite a read, and slaps every Hollywood “truthism” with data: marketing, stars, and opening weekends are actually statistical horseshit.

But there is one glaring historical example that anecdotally supports these claims (other than Star Wars, which is horrifically bad in literary terms), and it is Dumas’ “The Count of Monte Cristo”. When we perform literary criticism of the work, we see very clearly that is not only violates all the “conventions” described by these screenwriting “gurus”, but it’s actually not that good, in technical terms. The prose itself is fairly bland.

The characters are one-dimensional and predictable. There is little evidence of a 3-Act structure or reversal points (Dantes doesn’t escape until after the midpoint, no setback into III etc). He’s not a hero, and he’s not on a “journey”.

Carlos Javier Villafane Mercado described the effect in Europe when it was published:

“the serials, which held vast audiences enthralled … is unlike any experience of reading we are likely to have known ourselves, maybe something like that of a particularly gripping television series. Day after day, at breakfast or at work or on the street, people talked of little else.”

And of its legacy, George Saintsbury postulates:

“Monte Cristo is said to have been at its first appearance, and for some time subsequently, the most popular book in Europe. Perhaps no novel within a given number of years had so many readers and penetrated into so many different countries.” This popularity has extended into modern times as well. The book was “translated into virtually all modern languages and has never been out of print in most of them. There have been at least twenty-nine motion pictures based on it … as well as several television series, and many movies [have] worked the name ‘Monte Cristo’ into their titles.”

And this is CliffNotes’ explanation of why, despite how it ignores all the “formula” rules Hollywood lives by now:

“The greatness and the enduring popularity of The Count of Monte Cristo is mainly accounted for by the narrative force of the novel. In very simple terms, the novel tells an exciting story in an engaging and straightforward narrative — a narrative that grasps and involves the reader in the action. This novel is, in literary terms, a “well-made Romantic adventure story.”

Hundreds of books have been written as screenwriting guides for budding authors. Tens of thousands of words uttered by Hollywood leaders regarding established rules for box office success. God knows how many dollars spent by people trying to learn.

What we discover is that Goldwyn was right: nobody knows anything. At best, it’s a guess. But the painful reality is that the more we come to adhere to formulae and inaccurate collation of trends, the further we become divorced from the only known driver of artistic success: the story itself.

While we’re busy trying to fit ideas into templates for corporations (the “auto-tune” of cinema), in order to satisfy accepted “truths” that are devoid of any reasonable evidence, we are kneecapping the art of meaningful and compelling storytelling.